Sometimes when we’re far from home, it’s nice to have something familiar around to keep us connected. Contributor Eric Dregni has lived in Norway and Wisconsin. And by pure coincidence, he and his son have found a connection in both places with the same familiar thing: a stave church.

==

The first time my son, Eilif, and I saw a stave church from Norway was in Wisconsin. Eilif was just five and wanted to run, run, run and loved this building with menacing gargoyles jutting out of the eaves.

A young Eilif Dregni poses with the stave church at Little Norway in Blue Mounds, Wisconsin. (Courtesy of Eric Dregni)

We were in Little Norway, an old Norwegian farmstead near Blue Mounds and this creaky wooden building was a replica of the stave churches that date back nearly two millennia to the end of the Viking Age. A plaque outside said the church was built and shipped over from the town of Orkanger, the same place where Eilif was born when we lived in Norway for a year. No wonder Eilif had an affinity for this church.

The dismantled church originally arrived in Chicago for the 1893 World Columbian Exposition. Now…“Columbian” means “Columbus” and the Norwegians were not pleased. Didn’t everyone know that Leif Erikson beat Columbus by nearly 500 years? Besides, Leif didn’t brag so much about “discovering” a New World perhaps since people already lived here.

Little Norway’s stave church. (Courtesy of Eric Degni)

The Norwegian immigrants in the Midwest, however, wanted to make sure everyone knew. This stave church, along with a Viking ship that crossed the Atlantic, was that proof, that symbol. After the festival in Chicago, the stave church became a cinema and eventually moved to its new home in Little Norway, Wisconsin.

Then a couple of years ago when Eilif turned 15, we traveled back to big Norway to visit the town where he was born. We drove along the fjord from Trondheim to Orkanger to the Orkdal Sykehus, the hospital where my wife, Katy, gave birth. The Norwegian government not only paid for Eilif’s birth, but offered financial help for us new parents. If Katy had been working in Norway before the birth, she would have gotten 42 weeks off from work at full pay or 52 weeks at 80% of her salary—paid for by the government, not the employer. Since she hadn’t worked a day there, they gave us a cool $5,000 to help raise our baby. Not bad.

Little Norway stave church entrance (Courtesy of Eric Dregni)

I thought about my great-grandfather, also named Ellef, who fled Norway to escape poverty. Now, here we were admiring the generosity of the Norwegian system that helped new families rather than sticking them with a $5,000 deductible if they are “lucky” enough to have health insurance. What’s more, the Norwegian government deposited about $150 each month into our bank account to help raise baby Eilif.

It kept depositing money into our account even after we moved back to the U.S., so I had to compose a letter to them, “Please Norwegian government, stop sending us all your money.” (I sometimes regret sending that letter especially after doing the calculations of how much that would be after 15 years). Norway seemed generous by sending us this money and that replica stave church in 1893.

Gargoyles atop Little Norway stave church (Courtesy of Eric Dregni)

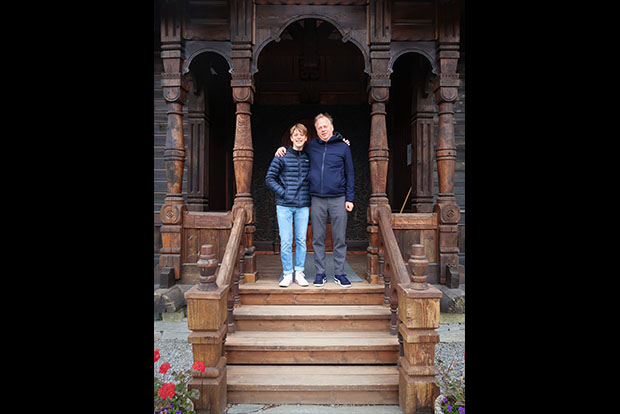

Eilif Dregni’s triumphant reunion with Little Norway stave church in Orkanger, Norway (Courtesy of Eric Dregni)

As Eilif and I drove from the hospital in Orkanger, we spotted that very same stave church that we’d seen before, but never here. Apparently after 122 years in the Midwest, Wisconsin’s stave church “went home” to Orkanger after Little Norway closed.

A group of Norwegians traveled to Wisconsin to dismantle the stavkirke church and lovingly restore it as a little bit of the Midwest in Norway — just as Eilif was born in Orkanger, grew up in the Midwest, and has now returned.