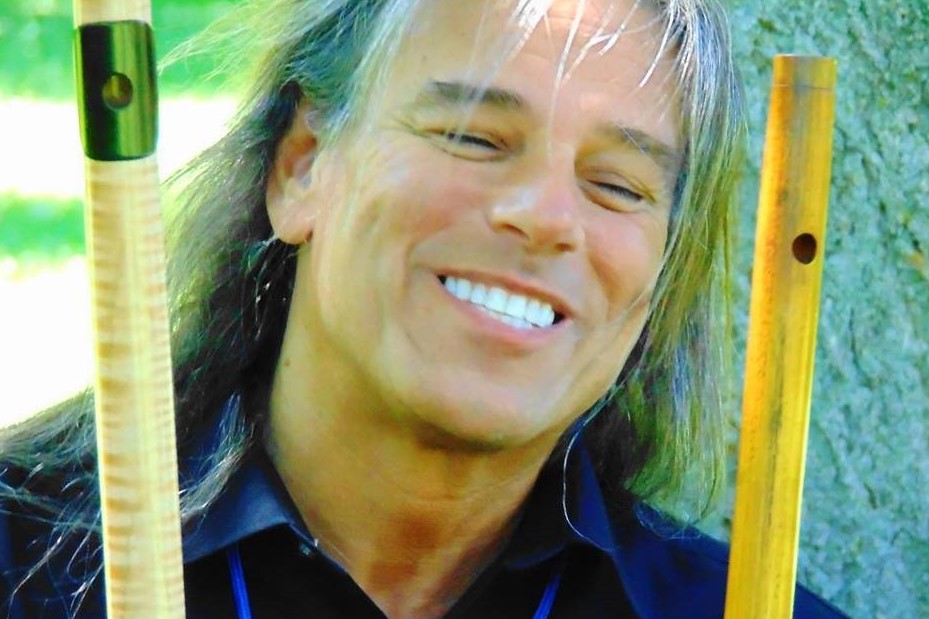

The flute is one of the oldest instruments in the world, after the human voice. Almost every culture has their version of one and, chances are, flutist Peter Phippen wants to play it.

The Eau Claire musician has spent the last three decades playing and studying flutes from around the world. He’s been nominated for a Grammy and a Native American Music Award. Ahead of the World Flute Society Convention at UW-Eau Claire this year, Wisconsin Life’s Maureen McCollum talked with Phippen about his music…..

(This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.)

Maureen McCollum: When did you start playing the flute?

Peter Phippen: Thirty-one years ago, I was on tour as a bassist in a rock band. We were playing all over. After 60 or 90 day tour, I’d promise my wife I’d buy her something. She wanted a sofa. So she dragged me all over Eau Claire looking at sofas. The last place we ended up was a World Bazaar gift shop at the mall, it’s no longer there. They had a basket of bamboo penny whistles from India. I’m not lying, I failed the recorder or the flutophone, whatever they gave us back then in fifth grade. I could not play it. But I picked up one of these 25 cent bamboo whistles and the thing just started playing by itself. It thought it was pretty interesting, so I bought it.

A friend teaching art at UW-Eau Claire, who collected instruments from all over the world, heard me play this 25 cent bamboo penny whistle. The next day on his way to teach art at the university, he stopped at my door at 8 in the morning… middle of the night for a rock musician. He had bansuri bamboo flute from India. He sternly looked at me and say, “Peter, if you’re going to play the flute, play this one.” He stuffed it in my chest.

I’ve spent the last 31 years working on different embouchures because I like to play flutes from all over the place and many of them require different embouchures. And I work on tone.

I call them “humility sticks.” Even to this day, a flute I’ve had for 20 years or more will let you down if you haven’t been paying attention to it. Each instrument requires a great deal of time. It’s not like changing bass guitars in the middle of a show. You better know which flute you’re playing and you better have it dialed in.

MM: How do you channel the music within you through the flute?

PP: It’s not in me, it’s in the universe. I believe music is already there, floating around the world. It’s in the ether. What I try to do as a spiritual flute player is to tap into that. And if you can tap into that and ride it, it’s a bucking bronco. If you can hang on, some beautiful things happen. Magic happens. So, I’m just channeling. I’m an antenna. I can’t even say if the music I’ve recorded is my music. It flows through me. I play the moment I’m allowed to play.

I’ve seen classically trained flutists and Irish flutists who have great technique and great skill. They can play the same thing over and over again at amazing rates of speed. That’s not what I do. I go the completely other direction. I try to play long and slow and sometimes if a fast passage arises, it’s good to have some technique because if the music calls for a fast passage or the improvisation, then I’m able to pull it off. But I never go for that.

MM: What’s your favorite type of flute to play?

PP: The Japanese Edo period Shakuhachi is one of my favorite instruments to play. You can hear it on a song that came through me in the studio, “Lascauex.” To me that song has a darker edge.

I also like playing the North Indian bansuri, a bamboo flute. I like playing replicas of the Pueblo flute from the American Southwest, because you can’t have the real ones. That would date from 800 to 1200 Current Era. All the real ones are in museums and you can’t get your hands on them. But luckily, we’ve had some flute makers go into the museums and get permission and make replicas of them. Some people modernize them a bit, so you can play them with a guitar.

Look at a modern Native American flute. It’s nothing like the old ones. Up until 1960, the tunings were made by hand measurements. Some had western influence that wanted to play a diatonic scale, but it wasn’t quite on. You could cross finger it. Those are haphazardly tuned and those are the ones I like the best.

MM: I understand that most of the songs on your albums are improvised. Why is that?

PP: There are a few songs on my albums that are not improvisations, very few. Most everything I’ve recorded is improvised in the studio. I’ll work with a flute for a long time. I’ll have it all dialed in. Then, I’ll go in the studio. I have a handful of musicians who know how to do this with me. I’ll look at them and go, “C sharp minor. Go.” And that’s how the music happens.

Like when I play with Enrique Rueda, he lives in Madison, that’s how we record. My mentor, Tiit Raid in Eau Claire, that’s how we record. Rahbi Crawford from Viroqua, WI, that’s how her and I record.

The last album with Rahbi, Sacred Spaces, that was all one take. No second tries. We walked in, played it, and left. We thought one song wasn’t good enough. I came back two weeks later and it was fine. It’s just a perception thing.

I like the term space music, living music. I can’t play songs on my albums ever again. Luckily if a computer’s running, I capture magic. I’ll do a variation of those tunes at my live performances, but never exactly the same. Once in awhile I’ll still compose. I find it much easier if something falls out of the sky and it hits me on the head. Then I quickly record it or jot it down. But once I’ve played it and recorded it, then I’m sorry. People come ask me to play it. Then, I have to learn own material like a cover song.