In the 1880s, the eight-hour day emerged as the prime focus of the labor movement. Historian John Gurda reminds us of the tragedy that accompanied the fight in Milwaukee’s Bay View neighborhood.

We gather each year to remember a tragedy. The date is always the same—the Sunday nearest May 5—and the place is always the site of a vanished iron mill in Milwaukee’s Bay View neighborhood. Even the people are generally the same, a motley crew that includes union activists, professors, politicians, and assorted Bay View residents.

The tragedy we remember took place in the first week of May, 1886. For a few days in that long-ago spring, Milwaukee was practically unhinged. A general strike, affecting everyone from bakers to brewers, began on May 1 and soon brought the city to a grinding halt. On May 2, nearly 15,000 strikers staged the largest parade in Milwaukee’s history to that point. By May 4, after a series of less orderly demonstrations, Gov. Jeremiah Rusk had called out the militia. One day later, horrified spectators witnessed the bloodiest labor disturbance in Wisconsin’s history.

What issue could have aroused such passions? Nothing more or less than the eight-hour day.

Milwaukee was a stronghold of the Eight-Hour agitation that swept the nation in 1886. Most workers of the time routinely put in ten to twelve hours a day, six days a week, for only a dollar or two a day. Not surprisingly, they wanted an eight-hour day without a cut in pay. Labor’s core demand was expressed in a simple slogan: “Eight Hours for Work, Eight Hours for Rest, Eight Hours for What We Will.”

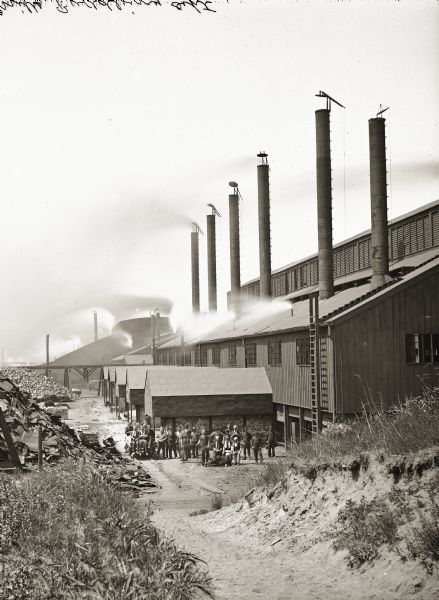

By the morning of May 5, unrest had shut down every major Milwaukee employer but one: a massive iron plant in suburban Bay View. The strikers resolved to bring the mill’s leaders to heel. Nearly 1,500 of them, mostly Polish immigrants, gathered at St. Stanislaus Church, on the corner of 5th and Mitchell, for a brisk morning walk to Bay View.

They found the militia waiting for them. The troops had spent an uneasy night inside the plant gates, and in the morning they received a chilling order: “Pick out your man, and kill him.” As the crowd surged down Bay Street toward the mill, the militia commander ordered them to disperse. At a distance of 200 yards, the marchers couldn’t possibly have heard him above their own noise. When they continued to advance, the troops opened fire. At least seven people fell dead or dying, including a twelve-year-old schoolboy and a retired mill worker who was watching the commotion from his backyard. The rest of the crowd beat a hasty retreat to the city.

The Bay View shootings ended, for the time being, the campaign for the eight-hour day, but they also galvanized Milwaukee’s workers. In the very next elections, the brand-new People’s Party won races for Congress, the state legislature, and Milwaukee County government. Although their triumph was temporary, it was the first tremor in a political earthquake that created the Socialist landslide of 1910.

We’ll be gathering at 3 P.M. this Sunday, May 1, on the corner of Russell and Superior, for speeches, songs, and a re-enactment. We’ll remember a tragedy, of course, but we’ll recall something even larger: the true cost of the eight-hour day.