The United States is a nation of immigrants and the pressure to assimilate can be great. Some people are compelled to speak English and leave other languages behind. Contributor Eric Dregni takes a look back at his own family’s relationship with language.

===

My grandparents spoke a mix of Norwegian and Swedish, or “Svorsk” as it was known. They used it mostly when they wanted an unintelligible language to keep secrets from the grandkids. How I wished they had passed on this language to me! Being second generation Scandinavians, they wanted to keep their distance from their immigrant parents, and their thick accents, and their Old World ways.

I used to believe this. I thought that the “old language” fell into disuse, and immigrants wanted to learn English. This perpetuated half-truth doesn’t tell the tale of government agents spying on Scandinavian and German meetings looking for socialists or anti-war activists. Settlers spoke English as a matter of self-preservation and any dissension was deemed unpatriotic.

My grandfather told me he could only speak Norwegian when he entered kindergarten and then would get in trouble since he didn’t know English. How could he? I begged my grandfather to teach me Norwegian, but he warned me: “We’re in America now. We speak English. It’s better that way.” Clearly he was scared of something I didn’t understand.

Then I discovered that some state governments set up a “commission of public safety” during World War I. Its purpose: to root out those deemed untrustworthy. It was mostly Germans — and Scandinavians by default — those with mixed loyalty who could be considered traitors. These commissions employed “virtually dictatorial powers to distribute pro-war propaganda and to restrict activities it considered hostile.”

These government agents infiltrated meetings and rallies to make lists of “radicals” and “slackers” as well as just plain “foreigners” who lacked enthusiasm to go to war. Because it was wartime, those who questioned could be locked up indefinitely.

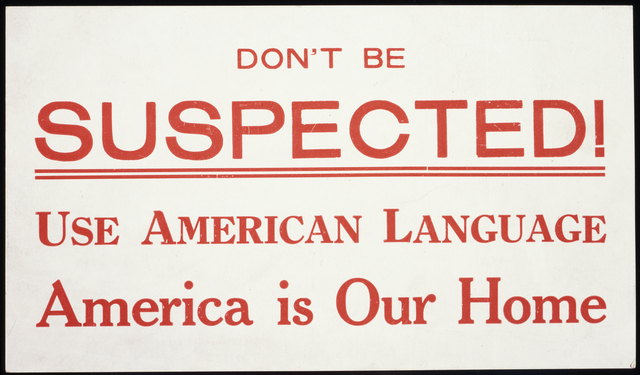

These commissions posted notices that read: “DON’T BE SUSPECTED! USE AMERICAN LANGUAGE- America is Our Home.”

Poster created between 1914-1918, Gift of Mrs. M.E. Palmer, Minneapolis, MN. (Courtesy of Minnesota Historical Society)

This was why my grandfather was afraid, but apparently his story was not unique. A young Swedish boy in Ashland, Wisconsin during World War I said, “We never speak Swedish on the street. Olof was roughed up by some of the Yankee boys in a restaurant last week.”

Because Scandinavian languages are somewhat similar to German, anyone caught speaking them was viewed as having “foreign sympathies” and a possible spy for Kaiser Wilhelm. Of course it didn’t help that the pro-Hitler German-American Bund set up Camp Hindenburg in Grafton, Wisconsin in the 1930s to help young German kids become good Nazis.

Up until the world wars, immigrants often had little incentive to learn English since most daily business transactions happened in their native language. Jim Jensen, a TV newscaster from Kenosha, said “If you went to the Danish Brotherhood, you spoke Danish. At church, the services, the sermon, my confirmation ceremony—all in Danish.”

Churches and social organizations tried to retain their language, although they were on the lookout for infiltrators. Many would begin conversations in English and then slip into their native tongue once they felt safe. Many churches switched services to English to show loyalty to the U.S., but mostly to avoid suspicion.

One Lutheran parishioner joked, “I have nothing against the English language. I use it myself every day. But if we don’t teach our children Norwegian, what will they do when they get to heaven?”

===

SONG: “re:member” by Olafur Arnalds