Imagine this: It’s early morning in a small Wisconsin town about a century ago. The sun hasn’t risen, but parents bustle around the kitchen.

They’re making pasties.

One’s for dad, who’s preparing for a day in the mines.

Some are for the children, who are about to head to their one-room schoolhouse.

The extras are for mom, who will warm them up for dinner tonight.

The pasty is convenient, hand-held, and delicious. It’s a flaky, buttery pastry folded over, pinched at the crust and bursting with meat and vegetables. The more traditional fillings might include beef, rutabagas, onions, and potatoes.

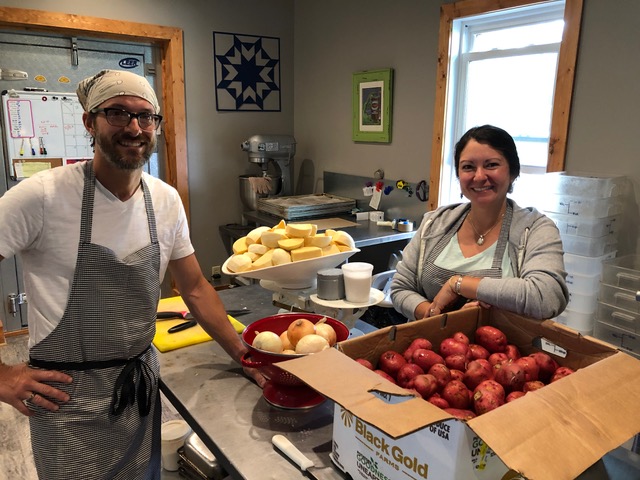

Joe’s Pasty Shop has been making these savory pies for decades. Jessica Lapachin opened a location in Rhinelander fifteen years ago.

“Joe’s Pasty Shop is a third generation pasty business,” said Lapachin. “My family opened up Joe’s Pasty Shop in Ironwood, Michigan in 1946. My grandfather and his brother, Joe, opened that shop. My parents own it and operate now.”

Miners from Cornwall, England flocked to Wisconsin in the 1800s. They settled in places like Mineral Point and Miner’s Grove as more lead was needed for things like paint, pipes, and lead shot. Cornish miners brought their mining expertise for extracting galena, which is a mineral used to make lead. They also brought a piece of their European culture — the pasty.

Interior of a lead mine in Cassville, Wisconsin. The five miners are holding candles or lanterns. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

“It’s a portable meal that the Cornish miners took down in the mine — a handheld meal that they could hold with dirty hands,” said Lapachin. “They would hold onto the crimp of the crust, eat the center and throw the crimp away.”

While pasties kept the miners nourished, they also thought the scraps could bring them good luck.

“There’s a superstition in mining culture of these spirits that live in the mine — they’re called ‘tommyknockers’ — they would do things like move tools around and hide things from the miners,” said Lapachin. “So, the miners started to think, ‘We have to appease them. Let’s give them the crust of our pasties!’ So they would toss them in the corners of the mines.”

When the demand for lead decreased in southwestern Wisconsin, many Cornish miners moved to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to work in copper and iron mines.

Pasties became a family tradition passed on from generation to generation. Lapachin says hers isn’t the only family with a pasty story.

“It’s a very familiar, memorable food for people,” said Lapachin. “They are really passionate about their favorite pasty, their pasty story and the way their grandmother made them.”

Woman wearing an apron fills a pasty in her Iowa County, Wisconsin kitchen. A man wearing coveralls is seated at the table watching. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

Inside Joe’s is regular customer LJ Summers. He didn’t grow up with pasties and had his first one when he moved to Rhinelander.

“Everyone in the neighborhood said, ‘You need to go get a pasty,’” said Summers. “I’ve been hooked ever since!”

Summers is now a pasty fanatic. He can’t stay away from the shop for more than a week. He loves the Greek pasty, but also likes to dabble in the Cornish one.

Even after the fall of the mining era in Wisconsin, people’s love of pasties lives on.

This story is a part of “Wisconsin 101: Our History in Objects,” a collaborative public history project created through a partnership between the University of Wisconsin-Madison History Department, the Wisconsin Historical Society, and Wisconsin Public Radio’s “Wisconsin Life” program.

==

MUSIC: “There’s Something About a Pasty” by Brenda Wootton

“Duke of Cornwall // Schindig” by An Ladron