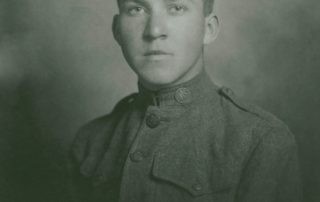

Bill Rice was just finishing his first year at Harvard Law School when he was accepted into the American Ambulance Field Service (AAFS) for a six-month tour as a volunteer ambulance driver. Rice was one of 325 Harvard men who served in the ambulance service prior to America’s entry into the war. Transporting the wounded from the front lines to the hospitals in the rear was the primary task of the American volunteers. Most of the driving was done at night without lights through fields and over shell-pocked roads. Many of the volunteers couldn’t drive despite requirements for driving skills.

After the U.S. entered the war, Rice returned to France and continued his service into early 1919. He wrote several letters a week to his parents. This one was written behind the lines at Verdun, the longest and largest battle of WWI. It’s read in the audio by Kristian Knutsen.

September 7, 1916

Dear Mother and Father:

We are still on post duty and today is the fourth day on which I have day duty (after twenty-four hours of no duty). These day duty days seem the best for writing, for other days, one is busy sleeping or with filthy hands working on one’s car. All the cars are getting verdunitis, from constant wear and frequent accidents. (No one is ever personally damaged.)

Just then I was interrupted by our excellent chief Townsend who sent me to my job of housemaid. The day squad, when not on actual service, has to sweep the house and clean up the yard. But I had no more collected my comrades than a loaded ambulance came down from the post and it was my turn to go up in its place. So now I am on the mountain side with the French artillery banging around me now and then, but things are pretty calm and cheerful. The sun is out, which makes life different from two nights ago when it was raining hard and cold and there were so many wounded that some could not be put under cover while being registered and examined.

You can get everything at the front, I should say, for it is always easy to send to Bar-le-Duc or some other town and get what you need. We have so little walking that our feet don’t tire at all. I wear wool socks in wet weather, however, because your feet inevitably get wet thru in the rain and mud after several hours. The four pairs of woolen socks you equipped me with are amply sufficient. And any you knit you would better give to civilian refugees, etc. I have your muffler to use when I need it, which I shall wear nearer my heart than I could socks.

Our work is sad, not so much because of the horrible wounds—they are already dressed before the men are brought to this post—as because of the deadening of life by constant contact with destruction and terrific physical shocks. The men are deadened, stupified. No one gesticulates; I used to think a Frenchman could not talk without using his hands. But the infantry is worn to the point where all joy has left life for the moment. Naturally the wounded, if not in great pain, are happy by comparison. They are going to be quite away from the war for a few days at least. The prisoners of course are in a similar situation. Many of them are working even right behind the front, harvesting, etc. But they are much relieved to be free of the strain of trench life or even shell-hole life, for such it is in this fierce vicinity. I rejoice more at the taking of prisoners than anything else; it is happiness for all and it saves a little of the youth of Europe. Everyone thinks more of the loss of life than of anything else.

Now that we have so much night duty, any one who has driven at night gets two fried eggs for breakfast besides the other regular viands. Let me reiterate; we are well fed.