Listen to Audio

Maureen McCollum:

Fry appears to have originated in the 1800’s, when the U.S. government forced many American Indians to move onto reservations. They were given commodities like flour, lard, and sugar to survive. Fry bread is become a staple in many Native American diets including in Katherine Denomie’s. She lives on the Bad River Reservation in northern Wisconsin but she’s originally from the Fond du Lac Band of Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. Denomie recently showed WPR’s Daniel Kaeding how she makes fry bread.

Katherine Denomie:

I’m making the dough right now. Measure out the flour, yeast, salt, sugar. Then put my oil and milk in there and mix it up. When I first started, I was about 19. My mom taught me how to make it. She taught all of us how to bake.

[scraping sounds]

So we wouldn’t starve I guess. I don’t know. [chuckles]

And I’ve had other women teach me through the years. We used to go to a lot of pow wows when I was younger. And I remember my mom being one of the main cooks for the feast. That’s all I remember is her cooking all the time.[chuckles]

So I knew because I can do it now, she’s the one that taught me.

[scraping sounds]

She taught me how to making a living anyways.[chuckles]

I’ve seen her cook a lot of food in my life for a bunch of people. I guess I got it in my blood. People always listen over a piece of bread. The young kids, they like to talk so that’s when you teach them. Keep their mouth full. Then they’ll listen. [laughs]

For me, it’s a living and it’s something that Indian people eat year round. It’s not just a special. It’s something we use every day. A lot of people don’t make it no more. Old ladies do but not the younger ones. I don’t know too many people that can make bread by hand anymore without a machine.

[scraping sounds]

And that’s it. And then I fry it. 400 degrees and then it cooks the bread. You cook it on one side and then you flip it over and you brown it on the other side. Then it’s done. It’s just the way we’ve known to make bread. We’ve had to make our bread over open fire. We never had ovens or anything so usually when you make fry bread, a long time ago, it used to be made outside. You used to put it over a fire and then a kettle, like a fry pan, and you would just put the whole thing in there. Not something you need to make in the house, or something, you can make it anywhere. So that’s why it was good for Indian people ‘cause they could make their bread anywhere they were camped at for a site. It only takes about a minute or two on each side. It’s good to go.

[Native American flute music]

Katherine Denomie lives on the Bad River Reservation in Northern Wisconsin but she’s originally from the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

When she was 19 years old, Denomie’s mother first taught her how to make frybread. She remembers attending American Indian Movement (AIM) pow wows with her mom when she was young. Founded in 1968, the organization protested on behalf of American Indian civil rights. The group sought protection of tribal sovereignty, treaty rights and restoration of their lands. Denomie’s mother was often one of the main cooks for the feast at the pow wows.

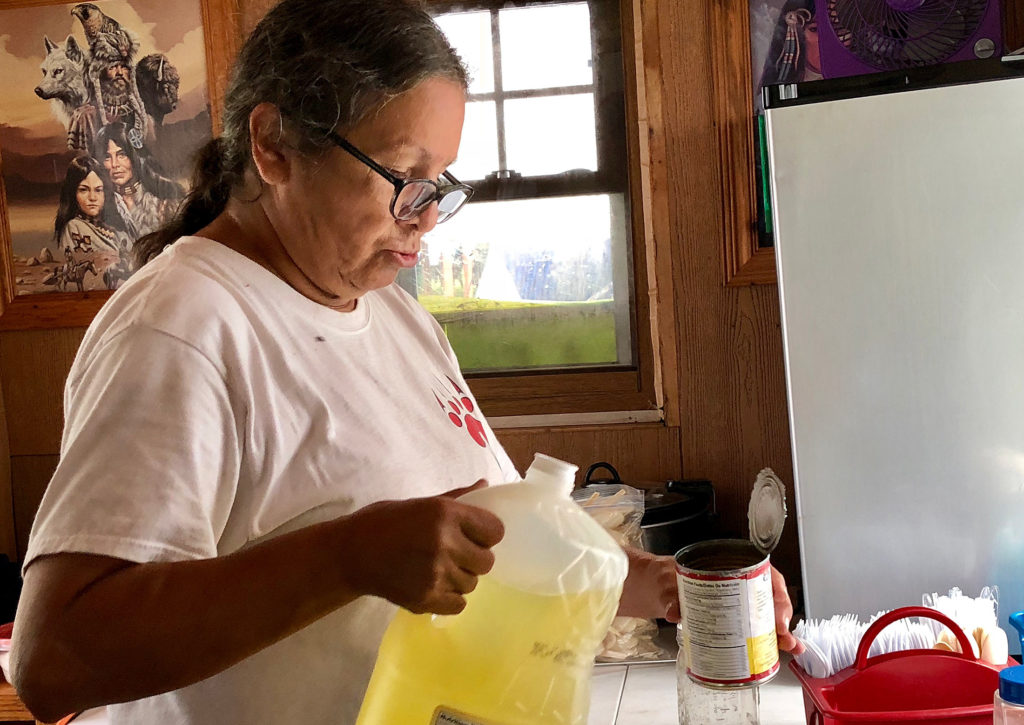

Denomie mixes flour, yeast, sugar, salt, oil and milk to make the dough for frybread. She lets it rise for about a half hour before she fries it in oil for a minute or two on each side. Denomie couldn’t remember her mom’s exact recipe so she turned to one on the side of a commodity flour bag.

For her, frybread is a way to make a living. She just began selling it as part of her business Denome Dough, which she started in July. “A lot of people don’t make it no more by hand,” Denomie said. “A lot of old ladies do, but not the younger ones.” Many years ago, people would make it in a kettle over a fire.

“You can make it anywhere. That’s why it was good for Indian people because they could make their bread anywhere they were camped at,” she said.

Frybread appears to have originated in the 1800s when the U.S. government forced many American Indians to move onto reservations. They were given commodities like flour, lard and sugar to survive.

This story is part of Food Traditions, a multimedia project exploring food and culture across Wisconsin.