Most of the folks who live on Langdon Street along Madison’s Lake Mendota are short-timers: students or young professionals. But at Kennedy Manor, on the corner of Langdon and Wisconsin Avenue, many residents have lived in the same apartment for decades – some for as long as 40 years.

Jess Miller lives around the corner from Kennedy Manor. His curiosity led him to explore what makes residents want to stay.

==

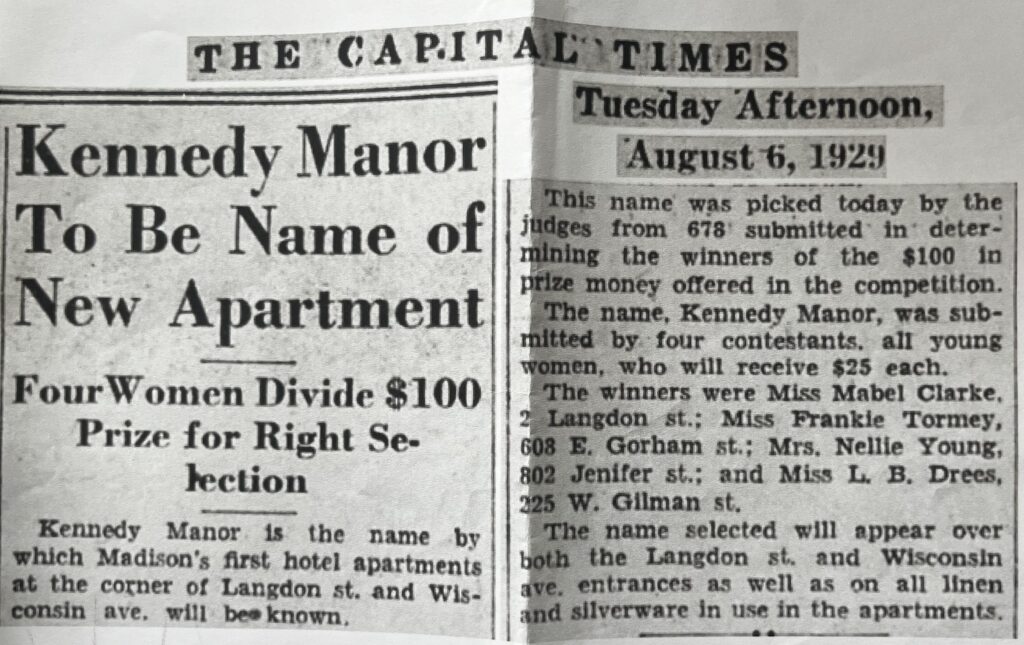

When Kennedy Manor was built in 1929, it was touted as the city’s first “hotel” apartment building. It offered housekeeping and a full-service restaurant and bar.

An August 1929 issue of the Capital Times announces Kennedy Manor as the name of Madison’s first “hotel apartments.”

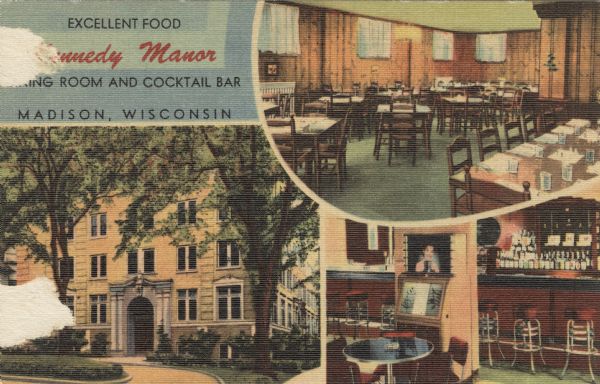

Over time, most of the building’s luxury amenities have gone. The restaurant, once a popular meeting spot for residents and locals alike, shut down in the 2010s. And maid service was discontinued during the pandemic.

But residents have stayed. In part because of the lower-than-average rent prices for the area, but also because of the views many apartments have of the lake or the Capitol building.

Three views of the Kennedy Manor Dining Room and Cocktail Lounge: exterior of front of the building, the dining room, and bar area with jukebox. Located at 520 Wisconsin Avenue and One Langdon Street. Caption reads: “Excellent Food, Kennedy Manor, Dining Room and Cocktail Bar, Madison, Wisconsin.” Photo courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society

“I remember moving in and saying to myself — it was June — and I said, ‘The first snowstorm, I’m calling in sick from work because it’s like a snow globe here,’” said Liz Allen, who moved into her one-bedroom apartment in 1987.

Many tenants say they’ve stayed because Kennedy Manor has allowed them to live the lives they want to live.

“I hope to either die at work or die here,” said Allen.

Historically, Kennedy Manor attracted prominent members of Madison’s upper crust. When Allen arrived, she observed that residents fell into one of three factions.

“There were the legislators. There were the old Madisonians. And the third were middle-aged eccentrics,” said Allen. “And I was in the middle-aged eccentrics [group]. And I’m now in the old-age eccentrics.”

Today, eccentrics thrive at Kennedy Manor. They’re artists and amateur historians. Multi-instrumentalists and activists. Whatever their passion, they’re free to pursue it.

Wes Freeman is one of the building’s newer faces. He moved in during the COVID-19 pandemic. His studio apartment doubles as a living space and the headquarters for his film production company. He’s currently working on two documentaries, so he spends a lot of time at the nearby University of Wisconsin-Madison library.

“Everything’s within walking distance that I need,” said Freeman. “If I really need to go someplace, I can get a neighbor from Kennedy Manor to take me.”

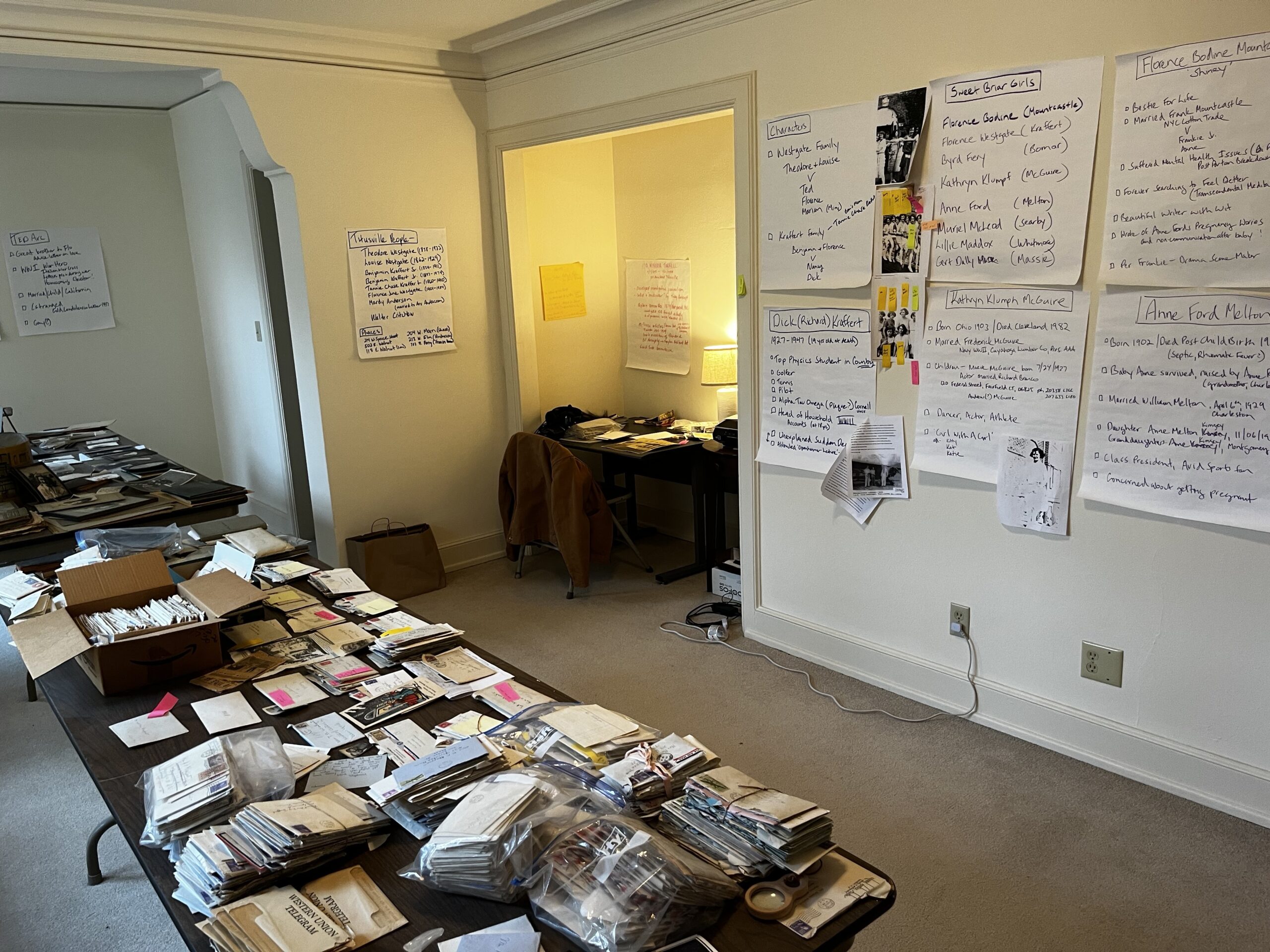

Anne Goodwin has two apartments in the building: one where she’s lived part-time since 2013 and another that she started renting in 2021 to use as an office for a family history project. Goodwin inherited hundreds of her late grandmother’s letters, photographs and personal objects. During the pandemic, Goodwin rediscovered the letters and started blogging about them.

“What I do is I take something that I know happened as a fact,” said Goodwin. “Like, for instance, my grandmother was engaged to two men at the same time. And then I use my imagination to create scenes around those little nuggets.”

Goodwin has described her apartment office as “a crime scene that we’re trying to solve,” with letters and paraphernalia spread out on tables and notes taped to walls. She and two collaborators have created a podcast inspired by the letters called “Meet Me at the Wall,” which launched on Jan. 12, 2025.

Anne Goodwin’s second apartment in Kennedy Manor is an office for her historical blog and podcast. Jess Miller/WPR

Resident Chelcy Bowles moved into Kennedy Manor in 1994.

“I met my husband the first year I moved to Madison, and we actually got married in the restaurant downstairs,” she said.

Bowles, an Irish musician, plays the harp and hosts music sessions in her apartment.

“During the pandemic, they let me have people in there so we could spread out really far,” said Bowles.

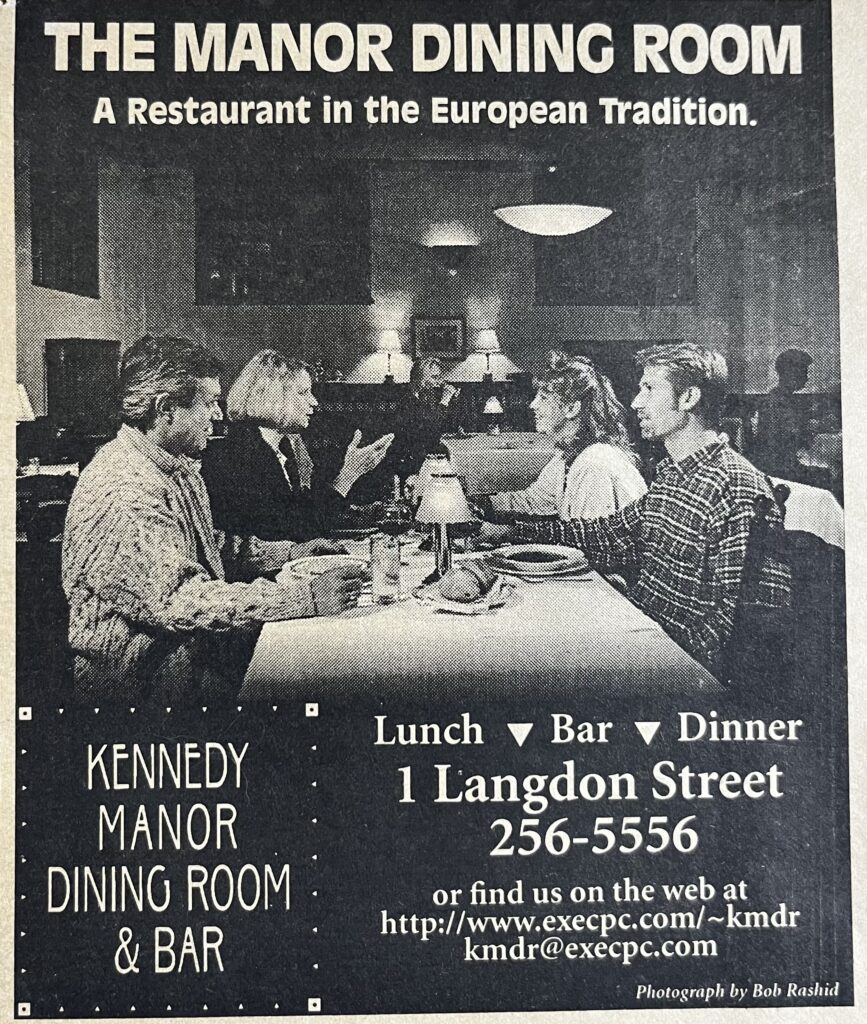

An early 2000s newspaper ad for the Kennedy Manor Dining Room. Chelcy Bowles, who moved into the building in 1994, is seated at left with her husband. Photo courtesy of Jess Miller

And Chris Allen — who is resident Liz Allen’s first cousin once removed — is also a musician. He came to Kennedy Manor in 2008 to get a doctorate in classical guitar performance at UW–Madison.

“The first night that I was here in the building, I took my guitar up to the roof and started to play. [I] asked a couple if they mind if I play some Bach,” he said. “And Chelcy said, ‘You must be Chris.’ They all knew that I was coming.”

Living in such close quarters for so long, people get to know each other well. And they look out for each other. Liz Allen remembered one former neighbor who was in his 90s.

“I would invite him over to watch the sunset. He loved it. He’d shuffle over. We probably would see each other almost every day. And his family knew something was up — this confirmed bachelor. And he wondered if I would want to marry him,” Allen remembered. “I said, ‘Well, it’s tempting. You’re 95. You’ve probably got some money shucked somewhere. I just don’t think it’s a good idea.’”

Liz Allen’s one-bedroom apartment in Madison’s Kennedy Manor is one of few in the building that features built-in shelving, installed by an affluent former resident. Jess Miller/WPR

Kennedy Manor might not be the idyllic living arrangement it once was when it once had the amenities. With the restaurant closed, the only cooking takes place in the apartments’ slim galley kitchens. Since maid service stopped, residents ride the building’s original 1929 elevator to the basement to do laundry in shared machines. And living at the end of UW–Madison’s fraternity and sorority row has its downsides, says Bowles.

“I don’t particularly like the really late at night stuff,” said Bowles. “Well, I would say early morning stuff.”

But she, like Chris Allen and so many of her neighbors, wouldn’t trade it for anything.

“I love it,” Allen said. “It’s home.”