Perhaps no American historian stirs a more impassioned response than Frederick Jackson Turner. His ideas about the western frontier were both admired and maligned, sparking controversy across decades. He wasn’t the first American to call attention to the frontier, but he was the first to say outright that the frontier explained America.

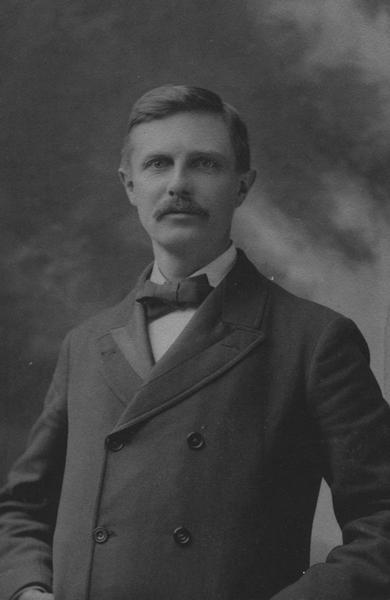

Turner was born in Portage in 1861. His father was a journalist and an amateur local historian, inspiring his son’s interest in history. After earning his Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins, Turner began teaching at the University of Wisconsin in 1889. Only four years later, he delivered the paper that would make his name.

Turner believed that American strength and vitality lay in its vast frontier. The problem for Turner was that in 1890, the Census Bureau stated that the all of the land within the United States was claimed – that there was no longer a frontier. Turner delivered the news to historians during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago where millions had flocked to see such wonders as a reproduction Egyptian temple and new inventions like the Ferris wheel, the electric dish washer, and the zipper. For Turner, the Fair was also the end of an era.

Turner’s lecture, “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” mournfully proclaimed the frontier closed. He questioned how American culture would develop and whether something of the American character – its coarseness, individualism, and strength – would be lost as a result. His paper was both an analysis of the past and a warning for the future. Turner’s lecture was mostly ignored at the time but it soon became one of the most influential pieces of historical writing in American history. It also shaped popular conceptions of the west and the types of people who live there.

The frontier wasn’t Turner’s only explanation for the uniqueness of America. He also attributed it to sectionalism, or groups of states with similar resources that were often at odds with each other. He argued that these sections were more important than states in shaping American history. It was this idea, which he put into a book called The Significance of Sections in American History that won him a Pulitzer Prize in 1933.

Turner didn’t live to see his award, though. He died in 1932. That he won an award for a book was surprising in a way because Turner didn’t actually write that much. Besides his hobbies and his family, he devoted most of his energy to teaching. He was adored by his students for his intellect, encouragement, kindness, and enthusiasm.

Turner still matters. In my college and grad school history classes, I couldn’t escape Turner. Agree with him or not, his ideas laid the foundation for the modern study of the American West not to mention his influence on popular culture. To have your ideas discussed more than a century after sharing them is no mean feat. As Turner said, “History, both objective and subjective, is ever becoming – never completed. The centuries unfold to us more and more the meaning of past times.” Turner offered us one story, one meaning. He pointed us toward an understanding of ourselves as a nation, a mythic West of noble cowboys, open spaces, and adventure that still informs our conceptions of ourselves as Americans.