Oshkosh is a Wisconsin town trapped in time – at least for me. I was born there, and proudly sported more than one pair of its bib overalls in my youth. My personal faves were the ones with the blue pinstripes. And while I spent a brief time in Milwaukee, grew up in the rural woods of Waunakee, and turned 18 in Middleton – I still consider Oshkosh my hometown. This was my safe-haven. My earliest memories were firmly rooted there. Unlike the other places, somehow I felt I could always return.

The neighborhood most etched in my mind is the Historic District, where my maternal grandparents, otherwise known as Gumma and Gumpa, lived. They lived on West Bent Avenue, right around the corner from the Paine Art Center and a few blocks walking distance from the Oshkosh Public Museum. Luckily, these two little gems remain today – despite a nasty fire that destroyed the third floor of the museum back in 1994. When my grandparents would take my brothers and I on walks around their block, we’d climb on top of the stone posts at the driveway to a church on the way to the Arts Center, and strike poses like statues.

This driveway had once led to a lovely old house that belonged to a member of the House of Representatives, William Steiger. He died of a heart attack at the age of 40 and the property was eventually taken over by a church. There was a secret garden in the back, nestled in tall Cedar bushes, with a bench and table. Gumma and I would pretend to have tea.

She took me to the Paine Art Center nearly every year. Lumber baron Nathan Paine was a prominent businessman in town in the early 20th century. He imported lavish furniture and art from Europe to decorate his Tudor dream house. But the Great Depression hit the company hard and construction abruptly stopped. When the Paines returned to the project in the 1940s, they turned it into a facility for the public. However, Gumma knew a far more interesting story about the place. She’d heard that Paine had angered a number of the locals with some shady business dealings that cost them their money. These locals threatened to bomb the place if Paine ever attempted to move in. Paine was scared off, so the beautiful mansion was taken over by the city and reopened as a museum enclosed in amber. It’s said that some of the Paines never left, though, haunting the halls of their dream home. I liked Gumma’s story better.

Once when I was in a small upstairs room with stained glass, I swear I heard a loud snap. I turned to find no one there. That didn’t keep me away, though. I was probably quite scared at the time, but now I remember all of these things with a reverence. Perhaps that’s why we tend to idealize the past. Like ghosts, our memories often blur events and places together in our mind, so that they become fleeting, bendable things to mold more to our liking.

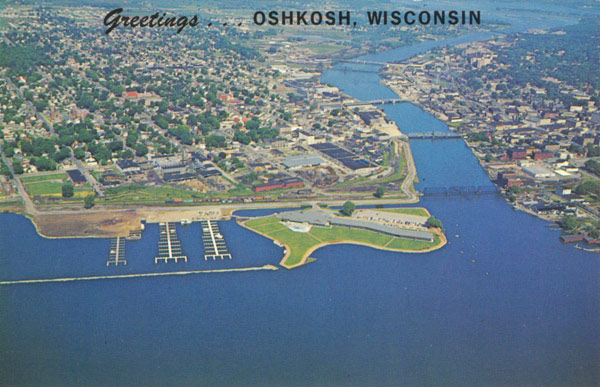

I don’t get back often, as most of the relatives have passed on or moved on. But every time I do cross over the bridge leading to the Historic District, I hear the familiar hum and can almost smell the remembered banana odor of the paper mill. I look out on the Fox River peppered with little fishing boats and smile. It can be ghostly returning to such a place with only echoes of memories past. But it remains for me a friendly ghost.