Mike Gomoll is not a rock star, but he knows how to get them to rally around a cause.

“You start out an email or a phone call with, ‘My five year old son died and I need your help,”’ he said, adding, “it doesn’t cost anything to ask people.”

In 2010, his son, Joey Gomoll, died – just one week shy of his fifth birthday – of a severe and rare form of epilepsy called Dravet syndrome. Epilepsy, most common in young children and older adults, is a chronic neurological disease that causes seizures.

Gomoll described Joey as a carefree kid who made the best of life, saying he was always laughing and smiling.

“With all of the terrible things life threw at him with the seizures … he was miraculously happy all the time,” Gomoll said. “He was in his own world, but he never had a down moment.”

That became clear when songs from the Teletubbies or Sesame Street’s Elmo would play.

“Music was Joe’s connection to the world,” he said. “He would grab everybody by their finger and make them get up and dance and kind of had this little boppy dance. And his word for dance was ‘dee-dee.'”

Joey Gomoll died of a severe and rare form of epilepsy just one week shy of his fifth birthday. His father, Mike Gomoll, founded the charity, Joey’s Song, in his honor. (Courtesy of Mike Gomoll)

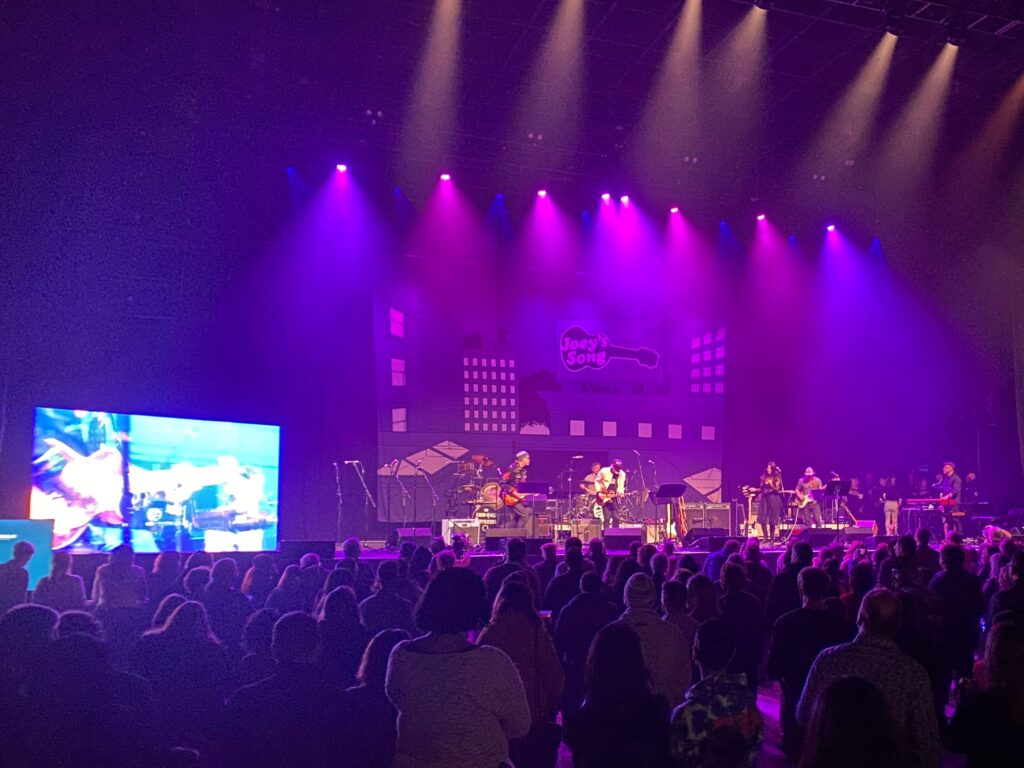

It’s part of the reason why Gomoll created a music charity in his late son’s name, Joey’s Song. The organization raises money through an annual concert to fund research grants and support programs for people with epilepsy. Since its founding, the organization has raised almost $1 million. This year marked the first time the benefit show was held at The Sylvee in Madison, where the venue sold out to 2,500 people.

Dr. Jeff Calhoun is one of the research grant recipients and made an appearance.

“Epilepsy is a devastating disorder. And we all have to do what we can to fight it. I do science. You guys have to help us, we can’t do it without funding,” he said at the event.

“It’s great that we can write their $100,000 grants. It’s great that we can write one. I’d rather write five,” Gomoll said.

“So the goal is to keep finding ways to grow the event and grow the fundraising,” he said.

Joey’s Song held its ninth benefit concert in 2023 at The Sylvee, where artists played to a sold-out crowd. (Gaby Vinick/WPR)

Rallying musicians to support the cause

Gomoll said there are plenty of causes to support, and he’s learned to not take no personally. Yet he’s successfully assembled an impressive lineup that would catch the eye of any 90s rock fan. Performers include members of Garbage, Soul Asylum, Belly and Fountains of Wayne. There’s also the Wisconsin musician super group, The Know-It-All Boyfriends. All of the musicians play for free.

Kay Hanley of Letters to Cleo was one of the performers at Joey’s Song in 2023. She said her daughter, Zoe Mabel, was having seizures, but nobody would call it epilepsy.

“No one would give us a diagnosis,” Hanley said, which only made her worry, “What is it? What is wrong?”

She said they found a specialist in Los Angeles who told them Zoe’s treatment had been “a failure.”

“We all burst into tears, but it wasn’t sad tears. It was happy tears because we finally felt like we were understood,” she said.

Zoe received a diagnosis about 13 years ago and got a VNS, a vagus nerve stem, which Hanley described as “a pacemaker for the brain.” Zoe’s epilepsy has been treated, Hanley said.

Still, Hanley said she didn’t know of any charities or organizations focused on epilepsy – until she came across her friend and Fountains of Wayne founder Chris Collingwood’s Instagram post about Joey’s Song. She said, “tell me everything,” and Gomoll followed up.

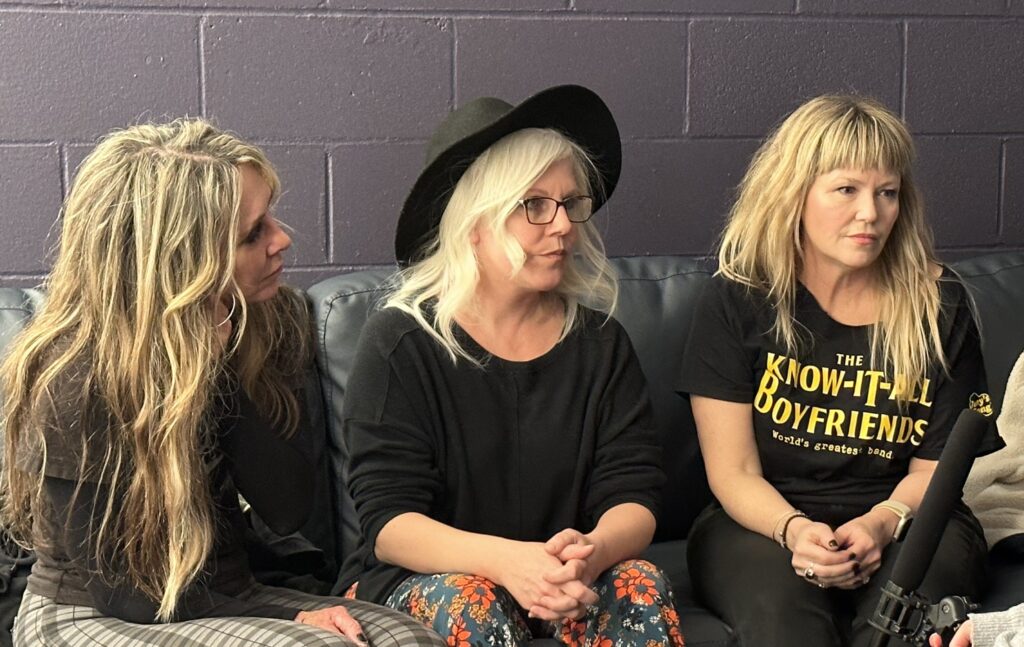

Seated in a dressing room at The Sylvee, (l-r) Gail Greenwood and Tanya Donelly of Belly and Kay Hanley of Letters to Cleo discuss why supporting Joey’s Song is important to them. (Gaby Vinick/WPR)

Hanley called up Tanya Donelly and Gail Greenwood of Belly to see if they could join her. Since the three musicians were in their early 20s, their respective bands have played together.

“We researched the charity. And we’re like, ‘Heck yes. What a wonderful foundation Joey’s Song is, and with a list of artists and to be able to play with,'” Greenwood said.

They laughed and agreed that Gomoll was also “aggressive” in getting them to play or, in nicer terms, “very enthusiastic.” The musicians sang and performed together at the concert.

Hanley said she is still learning about epilepsy, but it’s important to continue raising awareness.

The fight against epilepsy is also personal for Wisconsin native and Garbage drummer Butch Vig, the Grammy-winning songwriter and producer of bands including Nirvana. He said his sister-in-law and the best man at his own wedding, Bill Boyd, struggle with the disease.

The concert is also an opportunity for artists to collaborate and enjoy the music. “It gives us an excuse as musicians to just goof around,” Vig said.

He grew up in Viroqua and lived in Madison for 20 years before moving to Los Angeles. He’s been with Joey’s Song for seven years.

And like Hanley, Vig said Gomoll “doesn’t take no for an answer.”

For the 2023 show, Gomoll also reached out to Charlie Berens to offer some comedic relief at the fundraiser.

“My first reaction was, ‘Ah, geez, I don’t know if I belong there, you know?’ Because these are really talented people,” he said, quipping, “I mean, I’m good at fish and walleyes. But outside of that…”

Yet in all seriousness, Berens said he hopes people leave with more information on how to support people with epilepsy. He credits Gomoll for his perseverance and for “keeping his son’s memory alive in such a positive and cool way.”

Mike Gomoll successfully assembled an impressive lineup that would catch the eye of any 90s rock fan. Performers include members of Garbage, Soul Asylum, Belly and Fountains of Wayne. There’s also the Wisconsin musician super group, The Know-It-All Boyfriends. All of the musicians play for free. (Gaby Vinick/WPR)

Volunteers driven by mission

Stephanie Marquis is a PR executive and one of about 40 volunteers with the nonprofit. When she met Gomoll a few years ago and learned what his family had gone through, the story brought her to tears.

“As a mom, myself, I can’t imagine, you know, losing a child,” she said. Marquis said she saw her stepmom, who has epilepsy, experience a seizure.

“It’s terrifying. And maybe that’s part of the reason that people are afraid to talk about it. Because it’s scary when you see someone you love go through that and not be able to help them,” she said.

One in 26 people will get epilepsy in their lifetime, according to the Epilepsy Foundation.

In Wisconsin, about 60,000 people have active epilepsy, data from the CDC shows.

“The research dollars just don’t follow the prevalence,” Marquis said.

And aside from the opportunity to hang out with rock stars, Marquis felt driven by the mission.

“This is one of those things that we can actually do more research and potentially find a cure and find medications that can help because those medications haven’t changed for like three decades,” she said.

Gomoll said he had been thinking about starting a charity even when Joey was alive. But after Joey passed, Gomoll tapped into his Madison music scene connections to kickstart the organization.

“The prognosis then, and even today, isn’t really great. So we knew that there wasn’t a lot we were going to do to make Joe’s life better, even if he had survived,” Gomoll said.

Gomoll said he couldn’t wallow in the pain after mourning the death of his son. He emphasized that everybody grieves differently, but for him, “It was like, ‘Okay, let’s try to change something.'”

He started selling CDs but found that the events Gomoll paired them with raised far more money.

Years later, Gomoll said, he considers many of the musicians involved in Joey’s Song his friends.

“If we can make one family not go through what we went through through our efforts, then it’s worth whatever hours that we put into it,” he said.