In the mid-1970s, Lisa Chue Thao and her family had to leave their whole world behind. Their farm, their friends, their home. They lived in northwest Laos and the horrors of war were creeping in. So, they started walking and ended up in a refugee camp in Thailand. In the 1980s, Lisa moved to Eau Claire and raised her family there. She shares that experience in this essay, which she told to and is read by her daughter, Yia Lor.

==

When I walk along the Chippewa River, I’m reminded of another river in a place I once called home. Although thousands of miles away, kuv tseem nco. I have not forgotten the dirt path I walked to fetch water. I have not forgotten the stream that followed me to the garden. I have not forgotten my Hmong village in Laos.

When it happened, I was too young and didn’t know what to make of it. What child can piece together the meaning of war? My family lived in Sainyabuli Province. We were farmers and knew little about the world outside our village or the war that had begun before I was ever born.

One December night in 1974, some relatives came to say they were leaving. The war was coming. Teb chaws yuav tawg. Despite this news, my family stayed. We cut trees to prepare for our garden. We burned the land and planted rice. We were farmers, after all. Then in April of 1975, many Hmong people came to rest along the road by our house. They carried with them their belongings, and they delivered the same message. We cannot stay. We must go. The war is here.

I was nine at the time. My parents handed me my two-year old sister and asked that I carry her while they carried the rest of our belongings. Whatever we could not bring would be left behind. I tried to carry my sister but could not. My parents handed me some belongings instead, but they were too heavy. Feeling the weight of the world on my shoulders, I cried. I cried because I could not carry my sister. I cried because I could not carry our belongings. And I cried because I could not carry the life I only knew.

We left our village with hundreds of other Hmong people and never looked back. The paths in the jungles that we walked had already been paved by the hundreds that came before us. As we carried on, we cried.

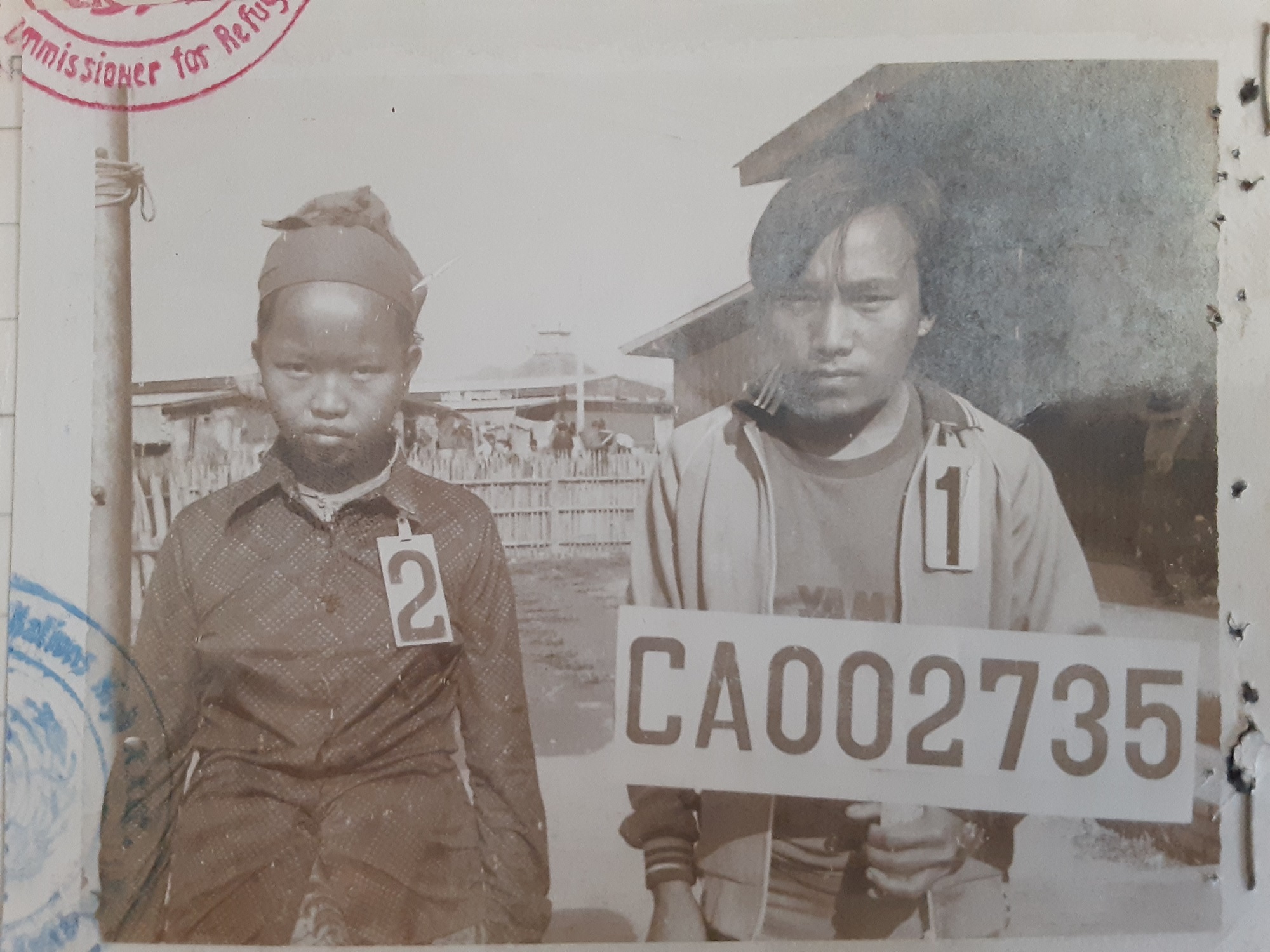

In October of 1976, we finally crossed the border into Thailand. It was in a refugee camp where I spent the rest of my youth trying to make sense of my past and look to the future. It was also here where I married my husband. One day, he suggested we apply for resettlement. We had an 11 month old son and decided we would go for our little family. We would go for those who have yet to come.

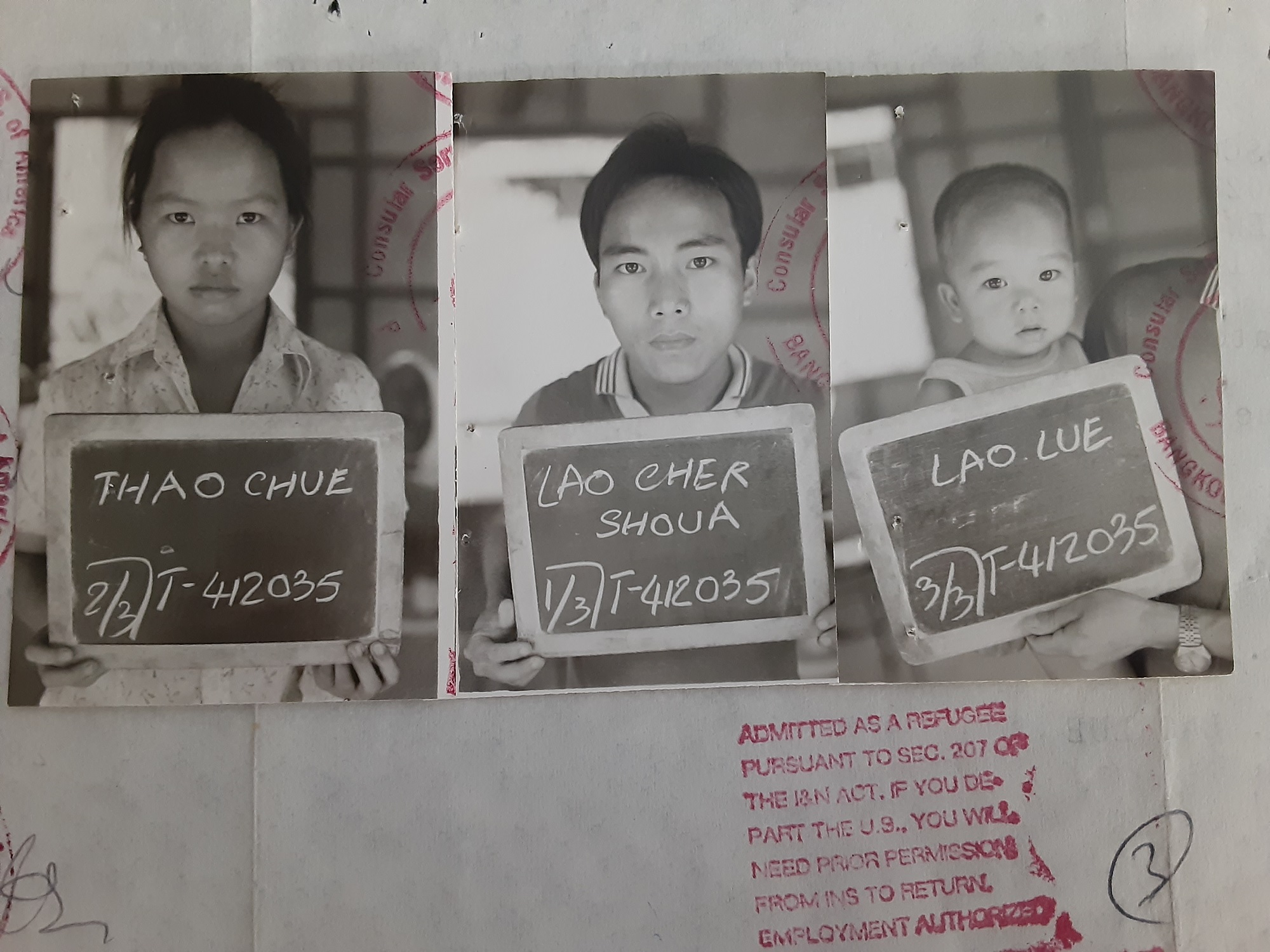

Lisa Chue Thao and her husband, William Shoua Lor, at a refugee camp in Thailand. (Courtesy of Yia Lor)

With that decision, we became names and numbers written on a chalkboard, paperwork filed away, a statistic, the aftermath of war. Perhaps the forgotten. Then in 1987, we were sponsored by a Catholic Diocese and left behind the land we first called home, a place where we played as kids, farmed and fell in love, and witnessed the death of those waiting for freedom.

America became my new home, and Wisconsin’s snow-covered hills and cornfields replaced the jungles and rice fields of Laos. I have tried to find my Hmong village on a map, but it is not labeled like Eau Claire. The river that ran through it is not drawn with a thin, blue line like the Chippewa River. Perhaps my village and its river no longer exist, but kuv tseem nco. I remember the dirt path I walked to feed our chickens and pigs. I remember the teapot we used to boil water from the stream. Thousands of miles and over fifty years later, kuv tseem nco.