The La Crosse area helped shape an historic politician, yet many people aren’t familiar with his story. George Edwin Taylor was the first Black person to run for U.S. president. To ensure that more people learn about his story, Taylor’s early life in western Wisconsin is now the subject of a new children’s book. WPR’s Hope Kirwan spoke with La Crosse author Darrell Ferguson about Taylor.

==

When La Crosse author Darrell Ferguson asks K-12 students to name the first person of color to run for president, the first name that comes to mind is usually former President Barack Obama.

“A lot of them are hard pressed,” Ferguson said. “They can go back to Jesse Jackson, some of those who are a little older. For those older ones, they may remember Shirley Chisholm.”

But the real answer is George Edwin Taylor, a newspaper editor and labor activist whose political career started in the La Crosse area.

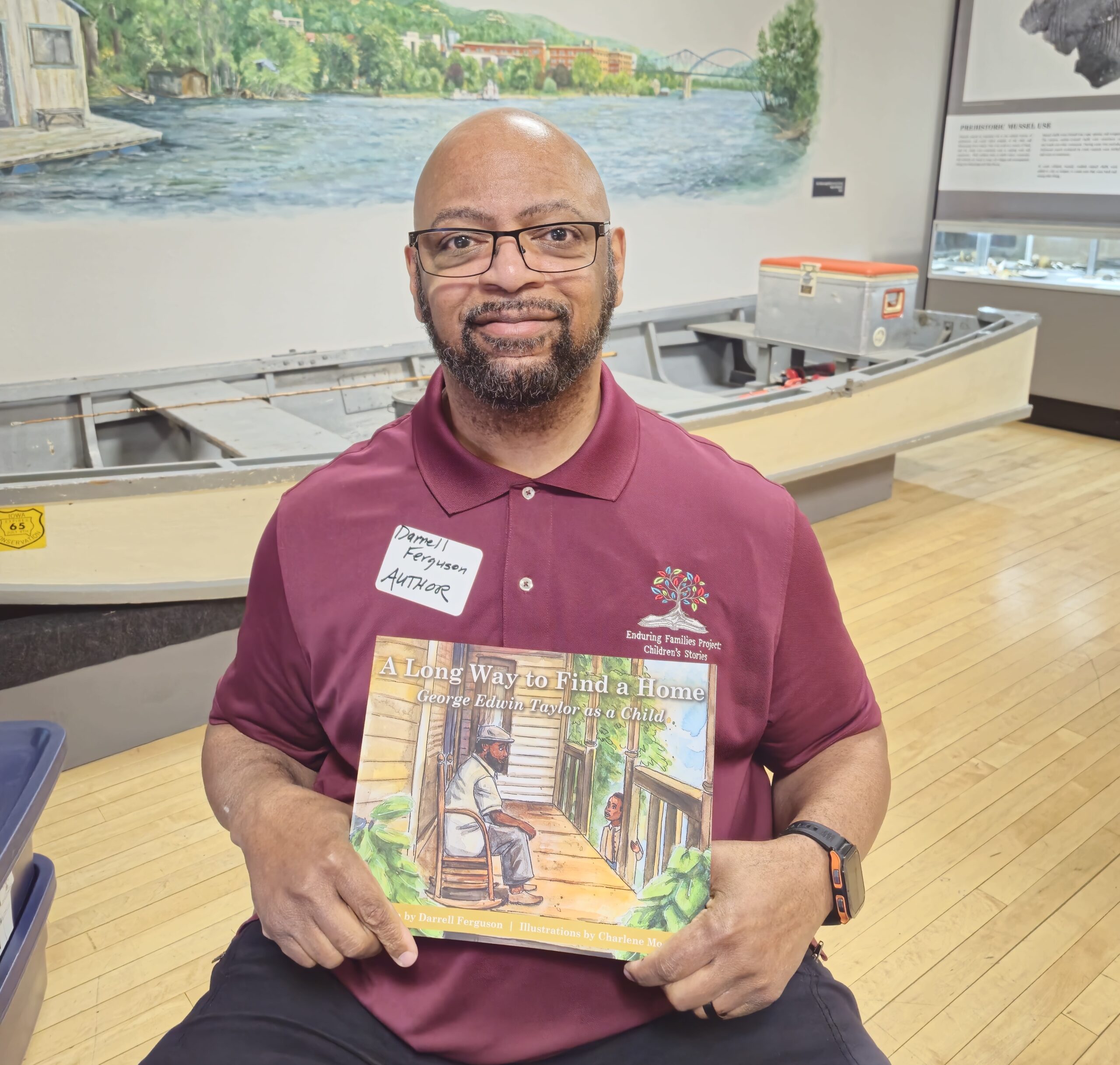

Taylor is the focus of a new children’s book by Ferguson, called “A Long Way to Find a Home: George Edwin Taylor as a Child.” It’s the first in a series of stories by the Enduring Families Project, an organization focused on preserving and sharing African American history in the Coulee Region of western Wisconsin.

Darrell Ferguson is author of “A Long Way to Find a Home: George Edwin Taylor as a Child”, the first in a children’s book series by the Enduring Families Project. Photo courtesy of Darrell Ferguson

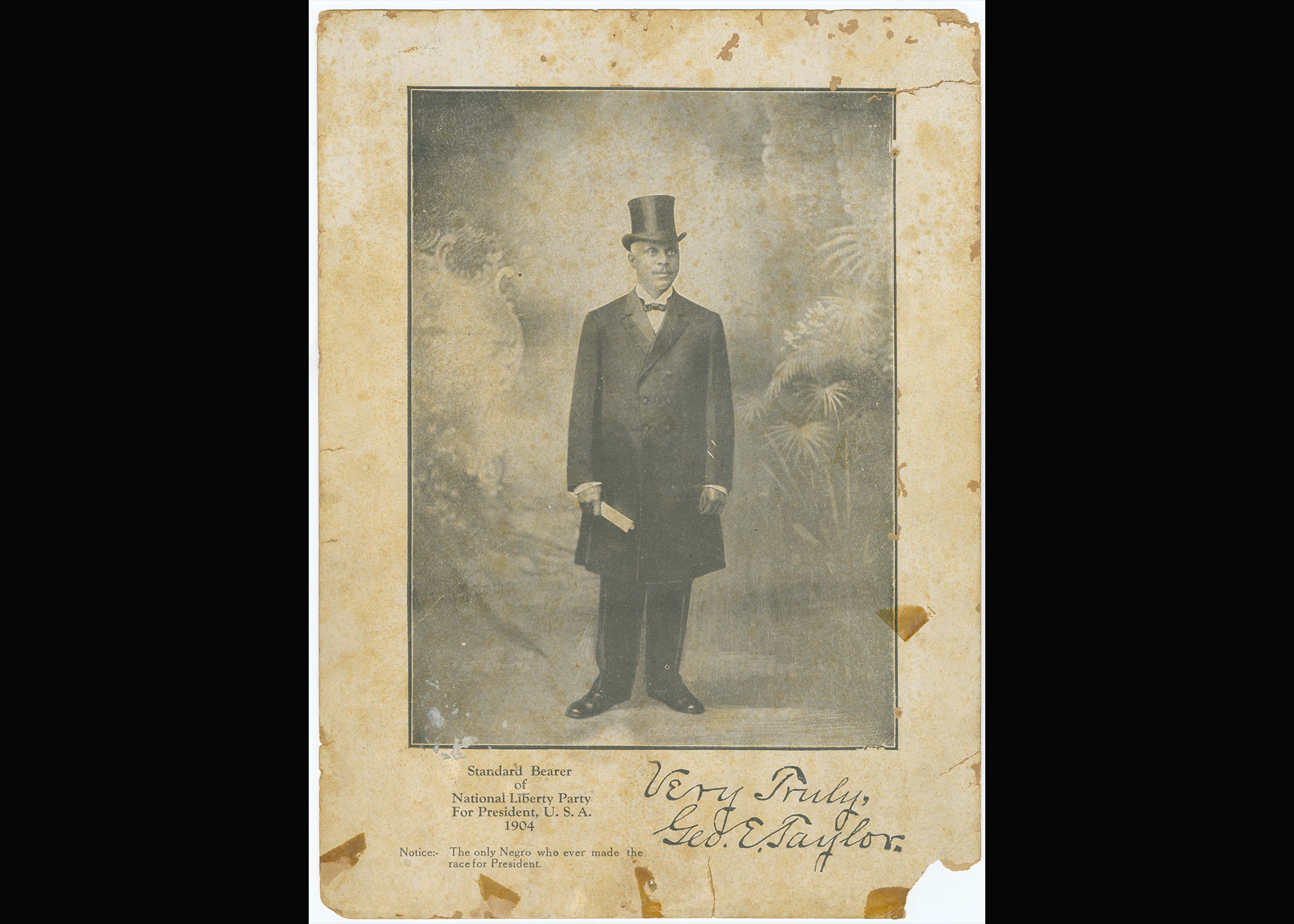

Taylor ran in 1904 against then-President Teddy Roosevelt. He represented the National Negro Liberty Party, an independent party that had formed that year by African Americans who were frustrated with both Republicans and Democrats.

But long before Taylor ran for the nation’s highest office, Ferguson believes the candidate’s politics were shaped by his difficult childhood.

Taylor was born in Arkansas in 1857, four years before the start of the Civil War, to a mother who was free and a father who was enslaved.

Two years after his birth, Arkansas lawmakers passed a law requiring all free Black people to leave the state. Taylor’s mother moved with her children to the Mississippi River town of Alton, Illinois, before dying three years later from tuberculosis.

“You can imagine a 5-year-old living alone in a city where he knows no one, and it was a struggle,” said Ferguson, adding that Taylor spent several years sleeping in crates along the town’s wharf, according to his account of his life.

Taylor finds home and purpose with La Crosse-area family

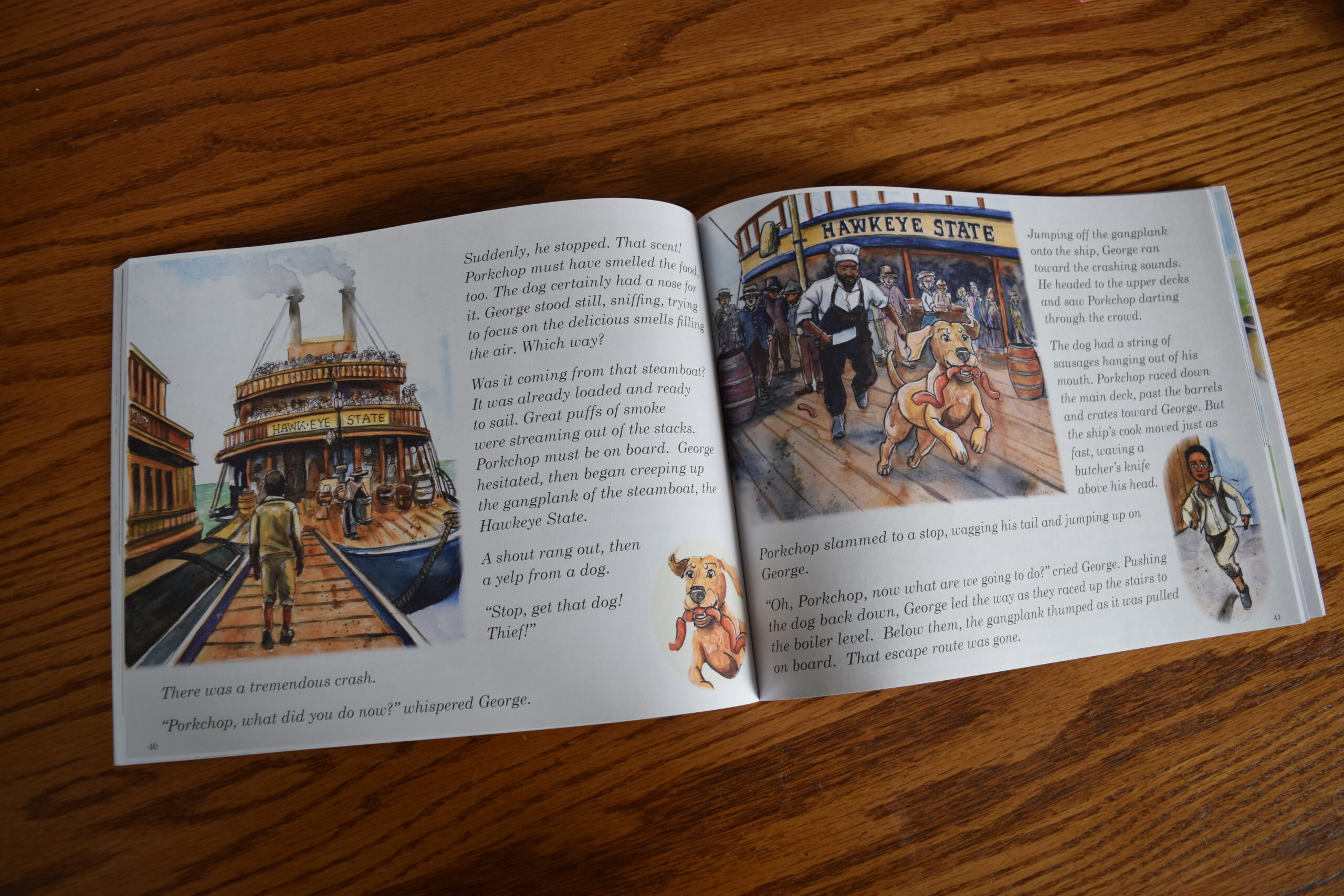

Taylor eventually stowed away on a steamboat called the Hawkeye State that was headed north up the Mississippi River. He arrived in La Crosse at the age of 8 and lived in the city for several years with different foster families.

After getting arrested at age 12, a local judge sent Taylor to live with Nathan Smith, a Black farmer and former enslaved person who took in a number of orphaned children on his farm near West Salem.

“Nathan was the one that George got to see had that involvement in the labor movement, in making sure farmers got equal rights and making sure workers got equal rights,” Ferguson said. “In one of George’s speeches, he basically focused on the fact that if the workers were to run the country, they would move the country in the right direction.”

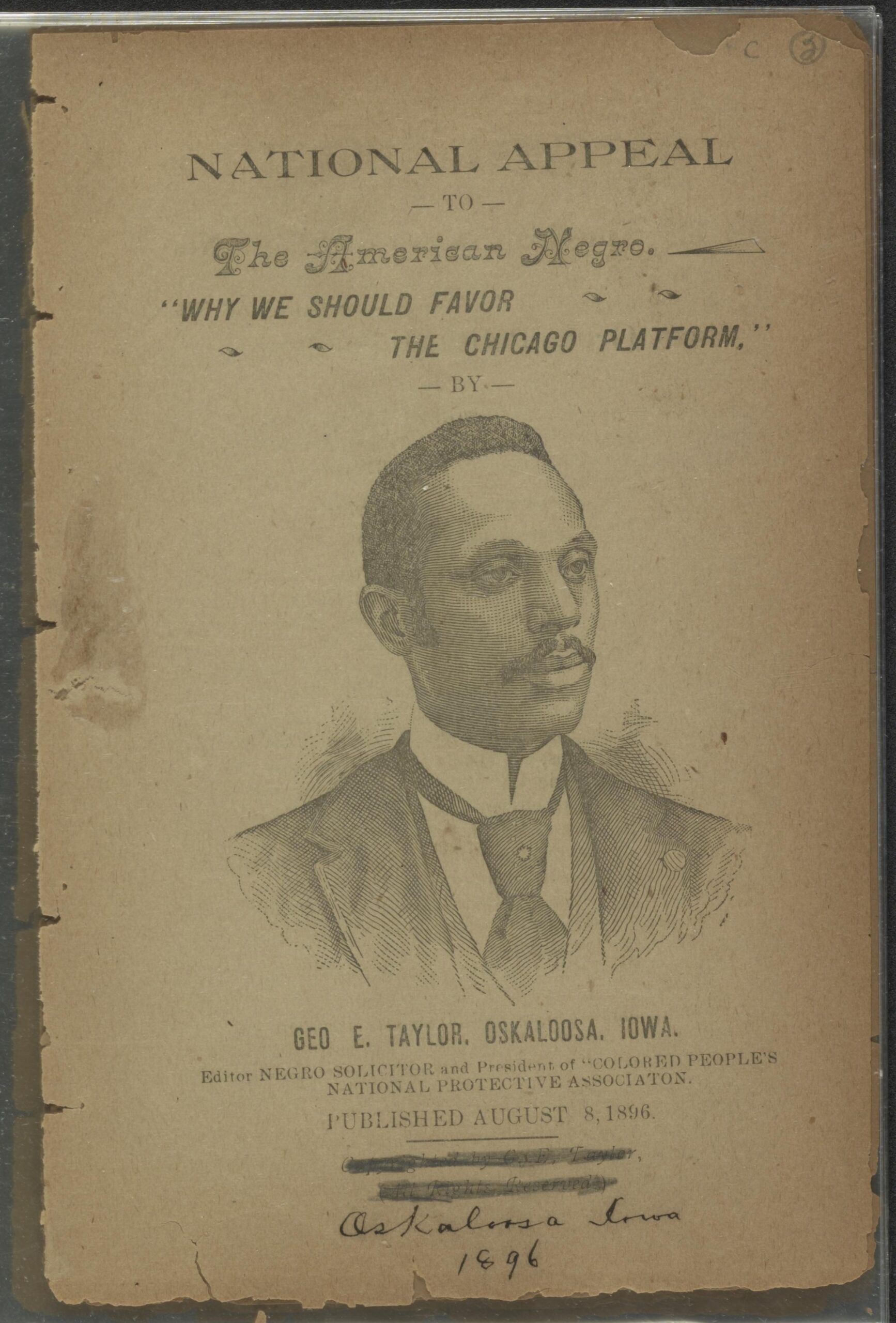

In his early 20s, Taylor moved back to the city of La Crosse to work as a newspaper reporter and editor. After several years, he became a leader in the Wisconsin People’s Party and later the Union Labor Party, publishing his own newspaper called the “Wisconsin Labor Advocate.”

A pamphlet written by George Edwin Taylor in 1896 urging African American voters to break from the Republican Party. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress

Taylor moved to southeast Iowa in his mid-30s to join a growing national Black political movement. He was active in both the national Republican Party and Democratic Party at different times, before helping to form the National Negro Liberty Party in 1904 to oppose Roosevelt in his reelection bid. The party called for equal rights under the U.S. Constitution and reparations for people who were formerly enslaved.

“(Taylor) was pretty prominent for his time period,” Ferguson said. “It just happens to be that he fell in that time period where news was not as nationally known as it is now.”

Ferguson uses fiction to go beyond the historical record of Taylor’s life

In the children’s book, Ferguson focuses primarily on the facts of Taylor’s life. He writes from the perspective of three children looking through historical records to answer their questions about how Taylor came to be a presidential candidate.

But for several key moments, Ferguson uses fiction to try to fill in the blanks of Taylor’s childhood. One of them is the first time he meets Nathan Smith, the man who would finally provide the boy a steady home and would eventually become Taylor’s adoptive father.

In the book, Ferguson imagines the stern talk Smith may have given the boy, who was used to fending for himself.

“‘… You need to decide: are you going to keep scratching and scrounging, or are you going to make a difference in this world?’

George rolled his eyes and looked away.

‘Sure, whatever you say. Can’t do much on a farm. A farmer can’t do nothing but work in the dirt.’

Nathan smiled. ‘Wouldn’t be so sure. A lot to learn from nature and the land. Nature ain’t gonna knock you to the ground for being who you are. She treats everyone equally and doesn’t care about the color of your skin.'”

“I created a dog for him (in Alton) because I thought he had been alone for so long, he may have needed a companion,” Ferguson said. “So I said, ‘OK, we’ll give him a dog, and we’ll name the dog Porkchop, because he was always hungry, and he loved pork chops.'”

A look inside the children’s book “A Long Way to Find a Home: George Edwin Taylor as a Child” by La Crosse author Darrell Ferguson. Hope Kirwan/WPR

Ferguson has spent years thinking about Taylor’s life through his involvement in the Enduring Families Project. He is one of several actors in the group who portrays Black leaders in early La Crosse through period costumes and monologues.

“I was George Edwin Taylor as the man going out campaigning, making these speeches and reciting these articles from my newspaper,” Ferguson said. “(Writing) this book allowed me to delve into him as a child and make the connection as to how he got to be that person.”

He worked with local historian Rebecca Mormann-Krieger to develop the children’s book series, which is designed to be used by elementary and middle school educators.

Ferguson hopes children who read the new book can empathize with or relate to Taylor’s experience overcoming difficult circumstances. He also thinks the story is a lesson for adults on the impact that kindness and generosity can have on the next generation.

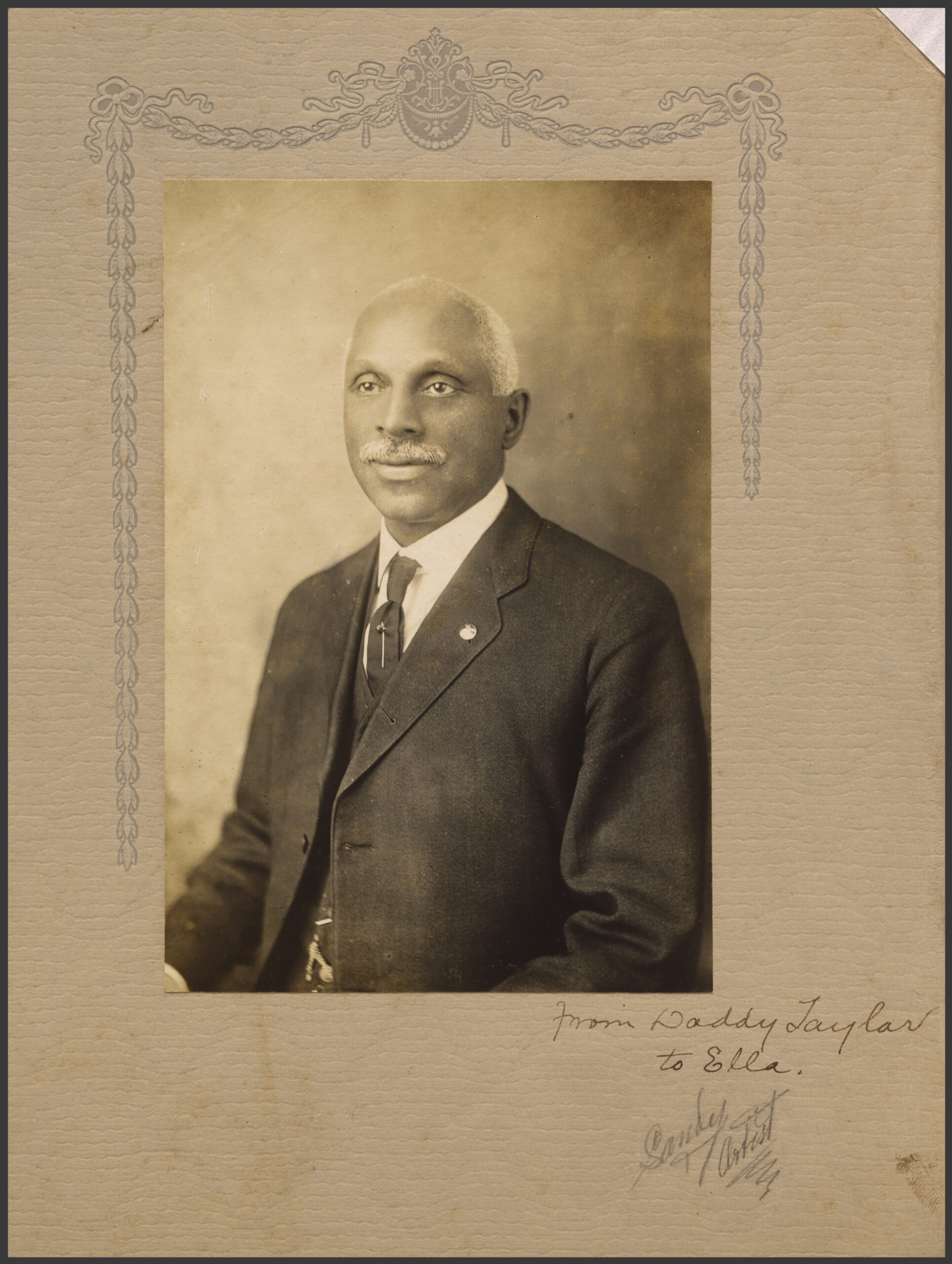

A portrait of George Edwin Taylor taken in 1910. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery