Winter slips and falls are dangerous and can be debilitating. While Milwaukee’s Shauna Singh Baldwin was recovering from her slip and fall, she discovered a Wisconsin community of support, ingenuity, and understanding.

==

From my high-rise window on a bright sunny day last January, I saw Wisconsinites pitching tents and ice fishing on Lake Michigan and motorcyclists zooming in circles on the ice. The temperature didn’t look anywhere near minus 20. I gave in to my urge to walk by the glacial blue eye on a plowed and salted walkway. It didn’t look icy — until my nose was five inches away from the thin veneer of ice.

The fall fractured my left radius — and I’m left-handed. I got a brace and sling. A week later, friends drove me to a very competent doctor who applied a hot pink cast. I could take the cast in the shower without wrapping it in plastic — it was made of anti-fungal material. My friends were disappointed they couldn’t sign it. Six weeks, the doc assured me, would go fast. Maybe for him.

Do you know how many activities there are for which we need both hands? As many as there are ways to compensate.

Can’t write longhand?

Thumb type into a notes app.

Dictate emails — voice recognition has improved.

Can’t wear a coat?

Wear a cloak.

Can’t hold the coffeemaker?

Order single-serve coffee packets.

Can’t use a can opener?

Buy pop-tops.

Can’t chop?

Buy salad kits and precut fruit.

This is Wisconsin, said my friends. Don’t we all know people who have slipped and broken knees, hips, or ankles? It could have been worse. They patiently ferried me to doctor’s appointments, the grocery store, the gym. East Side Senior Services volunteers also provided rides. A friend cooked Indian comfort food and stocked my freezer.

I requested help when folding clothes or changing sheets. I couldn’t hand wash, so I used paper plates and dishwasher-safe dishes.

Some activities like doing my makeup were difficult single-handed, but doable. Others were just not. I left some buttons unsewn, and hoped to resume playing my guitar and piano soon.

I marveled at the ingenuity of strangers who — with amazing forethought — had created assistive devices to make my life easier. Electric jar-openers, front-opening bras! The Americans with Disabilities Act had prompted improvements I now depended on: automatic doors, staircase railings.

The doc said I could drive if I wasn’t taking painkillers. My irrepressible uncle G. B. Singh, who lost his arm in World War II, used a Brodie knob on his steering wheel. And Wisconsin Medal of Honor recipient Gary Wetzel, who lost his arm in Vietnam, had a hook that enabled him to drive. Their fortitude and endurance in the face of permanent disability was inspiring.

Sure enough, the knob was available. I scrolled, admiring other ingenious assistive devices. Soon I had a strap with a handle, enabling me to pull the car door closed. My father-in-law’s Irish shillelagh would help me snag the seatbelt. They worked. I could drive!

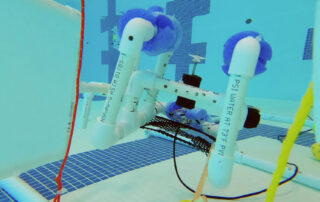

I shared my experience with Baljinder Singh, a sophomore studying bio-medical engineering at UW–Madison. He said designing assistive devices requires him to know physics, modern materials, computer science, the science of movement — and have empathy. For $150, his team recently modified a walker to obtain data from pressure sensors below its feet to show physiotherapists if their patients are improving. Humans, he feels, will always be better than AI at creating assistive devices for our bodies.

I’m relying on Baljinder and his fellow students to invent devices for me and fellow singletons as we age. Meanwhile, maybe I can now write convincingly about a character who slips on ice, breaks her arm, wears a pink cast for six weeks — but still drives, thanks to assistive devices invented by bio-medical engineers.

Editor’s note: Shauna Singh Baldwin is a member of the Wisconsin Public Radio Association Board of Directors.