Off a winding country road in rural Crawford County, the cave system known as Kickapoo Caverns has been attracting visitors since before Wisconsin became a state.

Historical records indicate the cave, which is one of the longest in Wisconsin, may have been dug open around 1840 by prospectors looking for lead ore. Before that, it’s unclear if the cave had a natural entrance to the surface. There is no evidence of Native Americans who originally inhabited the land visiting the cave.

For 100 years, brave visitors made their way inside with just lanterns or candles. Electricity and cement walkways were added in 1947 when the cave first opened as a tourist attraction.

The property still has picnic tables and restrooms leftover from its decades as a tourist attraction. (Hope Kirwan/WPR)

But even as the cave has changed hands through the decades, the underground world has remained a winter home for bats. While some bats fly south to avoid cold weather, four species in Wisconsin, including the little brown bat, big brown bat, tricolored bat and northern long-eared bat, call the state home all year round.

“They look for places to hibernate where they’re not going to freeze to death,” said Sarah Bratnober, communications director for the Mississippi Valley Conservancy, which currently owns the cave. “The temperature in the cave here is consistently around 48 to 50 degrees throughout the year.”

But what was once a haven for the bats became deadly in 2014 when a disease called white-nose syndrome arrived in Wisconsin. The fungus causes the bats to wake up early from their hibernation and can lead to the deaths of up to 99 percent of bats in a cave.

Protecting the bats at Kickapoo Caverns — and the wildlife habitat above — is why Mississippi Valley Conservancy purchased the property in 2017. The 80 acres of land are open to the public all year round, but Bratnober said her organization only opens up the cave for tours a few times per year. They discontinued the tours during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, but reopened the cave in 2023 for visitors from around the Driftless region.

Sarah Bratnober, communications director for Mississippi Valley Conservancy, prepares the cave entrance building for visitors on July 22, 2023. (Hope Kirwan/WPR)

Down a short path through the woods is the cave entrance building: a log cabin structure that once was a gift shop. Behind a metal door, cement steps lead below the ground, lit by small electric lights.

During a visit to the cave at the end of July 2023, Bratnober said local bats were roosting in the trees and eating up as many mosquitos as possible. But by October, they’ll start making their way into the cave through a small slot near the cave entrance.

Ducking under a low hanging rock, Bratnober leads the way down into the ground. The pathway opens up into a chamber with a ceiling around 15 feet high and a long fracture running the length of the cave. Bratnober said the crack is what allowed the cave to form, as water leaked in to erode the sandstone and limestone.

“All around us, we’re seeing kind of flowing forms of limestone that are being dissolved and forming these new sort of icicle-like shapes that are deposits of minerals that are coming down with the water,” Bratnober describes the space. “It’s very damp in here because water is a part of what’s going on, that created this cave and continues to shape it.”

Stairs lead down into Kickapoo Caverns, one of the longest cave systems in Wisconsin. (Hope Kirwan/WPR)

A cement staircase leads further down into the cave. The next chamber is even larger than the first, with 40-foot tall ceilings and dramatic lighting along the walls. Called the Cathedral Room by the original tour companies, the space still has an old cross that was installed at one end when the cave was rented out for wedding ceremonies.

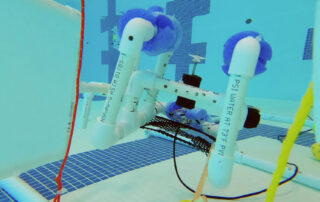

Underneath the steps, Bratnober points out a set of steel cages left by researchers from the state Department of Natural Resources and their partners. When Mississippi Valley Conservancy purchased the cave, Bratnober said they knew the fungus that causes white nose syndrome was present. Now they allow scientists to study how the local bat population could potentially beat the disease.

“A lot remains to be seen about how the bats will do with this fungus in the environment,” she said. “Will they develop a resistance to it? Is that why some of the bat populations in Wisconsin are coming back in the last year? We don’t know yet.”

Bratnober said Mississippi Valley Conservancy also tries to educate the public about the importance of bats to the state’s environment and what residents can do to support the struggling populations.

Sarah Bratnober, communications director for Mississippi Valley Conservancy, said Kickapoo Caverns is a great place to teach the public about protecting local bat populations and the area’s groundwater. (Hope Kirwan/WPR)

In a smaller chamber at the very end of the cave system, Bratnober points out a small pool of water, usually 8 to 10 inches deep, that’s noticeable between the rocks.

“There’s water coming in even now from above. Because of cracks and the dissolving of rock, that water also continues to go on down,” she said. “It’s probably going down as far as our drinking water most likely. That’s another important reason to conserve land around caves and sinkholes, to prevent chemicals and waste and runoff from going down those places into our drinking water.”

A sign warns visitors about white nose syndrome, a fungal disease that has killed hibernating bat populations in Wisconsin and across the country. (Hope Kirwan/WPR)

Bratnober said this fact is well-known by the residents of Crawford County, who continue to try to protect the porous landscape from pollutants. She said it’s likely part of the reason the conservancy received an outpouring of local support to buy the land when it came up for sale.

Bratnober said both the bats and the region’s groundwater make Kickapoo Caverns the perfect classroom.

“A lot of people have never seen anything like this before and kids who get the chance to come down here are really wowed by it,” she said. “What a great way to introduce them to some of these ideas about conservation.”

==

MUSIC: “Walls of the Cave” by Phish