Few jobs were as miserable and hot as work in a 19th century iron mill – especially in the summer. We may be sweating now but historian John Gurda tells about the workers who labored in unimaginable conditions.

All winter we longed for this: green grass, open windows, and heat, blessed heat. Now that it’s here, many of us spend our days moving between air-conditioned homes and air-conditioned offices in air-conditioned cars.

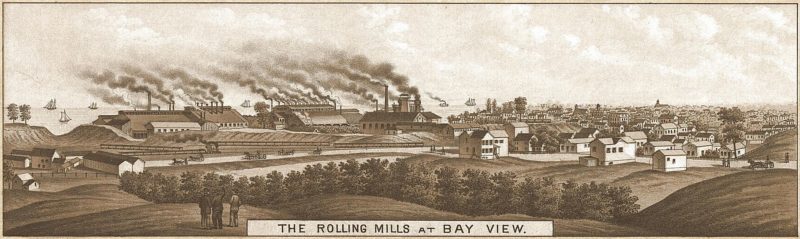

Our ancestors had no such options, especially if they wore blue collars. Some workplaces were practically hell on earth in summer, and Milwaukee’s most infernal employer must have been the Bay View iron mill. Opened in 1868, the mill dominated the south lakefront. Within a decade it was the second-largest source of railroad rails in America and Milwaukee’s largest employer by a wide margin, providing jobs for nearly 1,500 men.

It was not work for the delicate. In 1881 the Milwaukee Sentinel sent a reporter down to the mill during a heat wave. What he found would have horrified any modern health and safety inspector.

Puddlers, the skilled workers who tended the blast furnaces, routinely endured temperatures exceeding 160 degrees. They spent twelve hours a day, six days a week, producing caldrons of liquid iron.

Workers down the line fared no better. Some rolled red-hot ingots fresh from the furnace into rails, and others stacked them while they were still glowing.

The mill hands had few defenses. There were no electric fans because there was no electricity. The furnace men generally worked bare-chested, with Turkish towels wrapped around their necks to soak up some of the sweat. Every worker downed two to three buckets of “oatmeal water” during his shift, usually laced with lemon juice.

For this most hazardous of all hazardous duty, the skilled workers earned five dollars a day. That translates to only seven dollars an hour in modern terms, and the tradesmen received not one dime in fringe benefits. Unskilled workers earned a little over a dollar for their twelve-hour days.

Safely back in his office, the Sentinel correspondent could afford to wax philosophical. “No one is to blame for it all,” he wrote. “Railways must be constructed…. The men are satisfied with their pay and must be satisfied with the weather.”

The mill hands were a good deal less satisfied than the reporter suggested. The skilled workers organized a union called the Sons of Vulcan and in 1873 built a headquarters on St. Clair Street. Puddlers Hall is still in use as a neighborhood tavern.

The union was involved in frequent labor disputes. In 1873 nine heaters left their jobs to protest excessive temperatures. They were promptly fired, a move that stirred the union to call a walkout of 900 employees. Production ground to a halt.

One of the discharged workers, in a triumph of understatement, said, “The position of a heater is not an envious one…. In cold weather the perspiration steams from them, and in hot weather with no breeze it is scarcely bearable.”

The sweat kept pouring until 1929, when the mill closed for good. It was torn down a decade later, and the site is now largely green space at the south end of the Dan Hoan Bridge. Today only the ghosts remain.

So next time the mercury climbs past eighty, step out of your air-conditioned cocoon for a moment and raise a glass of oatmeal water to the mill hands of 1881. They were men of iron, wrote the Milwaukee Sentinel, “who become red hot and yet do not melt.”