There’s a peninsula just off Lake Michigan in Milwaukee that has lived many lives. Today, Jones Island is home to a sewage treatment plant, piles of salt and rail cars. But, it was once home to thriving communities.

Jones Island is also the subject of a new Milwaukee PBS documentary co-written by author and historian, John Gurda.

In “People of the Port: A Jones Island Documentary,” Gurda talks about the Potawatomi who lived there and used the area to fish, gather wild rice and race ponies. French Canadian fur traders eventually arrived. And after the Potawatomi were displaced, European immigrants began settling down on Jones Island and turned the space into a shipyard and a sportsmen’s haven.

Finally, as Gurda tells us, a Polish immigrant community flocked to the area. They were drawn in for the same reason as Jones Island’s earliest settlers — fishing.

Elevated view of fishing village on Jones Island, Milwaukee in 1892. Several fishing boats are docked along the shoreline. Large piles of lumber are in the foreground across from the island. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

==

It’s not a tourist attraction.

Jones Island lies just blocks from downtown Milwaukee, but visitors are few. What they see are freight yards, fuel tanks, docks, the Dan Hoan freeway bridge, and the largest sewage treatment plant in Wisconsin.

Here was the city’s front door in the Age of Sail, and here is the hub of its urban infrastructure today.

Jones Island Water Reclamation Facility, one of two treatment plants run by the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, is shown on Nov. 15, 2019. (Danielle Kaeding/WPR)

What it lacks in glamor, Jones Island makes up for in stories.

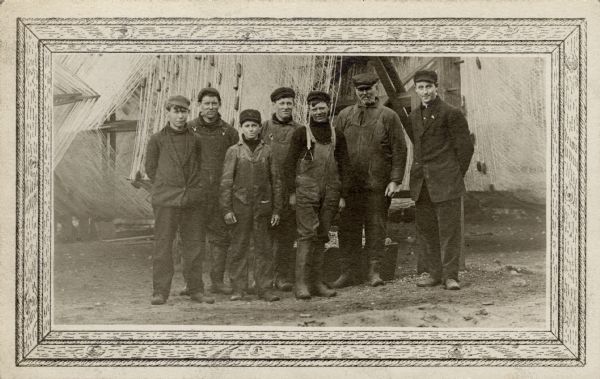

For nearly fifty years, from the 1870s to the 1920s, the peninsula was the site of a commercial fishing village settled by immigrants from the Baltic seacoast of Poland.

These Kaszubs, as they were called, numbered more than 1500 by the turn of the twentieth century.

First in rowboats near the shore, then in motorized tugs that chugged over the horizon, they brought up two million pounds of fish in a typical year, including lake trout, whitefish, herring, perch, and sturgeon. Their catch was a critical source of protein for Milwaukee’s growing population.

Man inspecting fish hung up to dry in a yard on Jones Island. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

Fishing also provided a livelihood for one of the most unusual urban villages in America.

Jones Island was a colony of squatters who occupied their land without benefit of title.

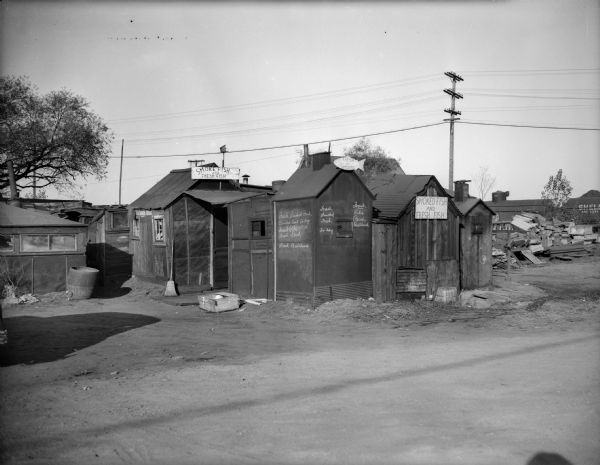

Their homes were makeshift, their street system was improvised, and their shoreline was a maze of fish sheds, boat houses, and massive wooden net-drying reels.

The setting was so picturesque that artists from the mainland were among the most frequent visitors.

What they found was a complete human community. Jones Island was a complex web of interrelated families who supported social clubs, a baseball team, a chorus, and a total of eleven saloons, each serving its own version of the Friday night fish fry.

Signs for Kingsbury Beer and politicians are in the window of a storefront on Jones Island. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

The Kaszubs were also faithful members of St. Stanislaus Catholic Church. Whole families could be seen every Sunday morning rowing across the Kinnickinnic River in their finest clothes to Mass on Mitchell Street.

Jones Island may have been picturesque, but its days were numbered.

As mainland Milwaukeeans enjoyed electricity, running water, and indoor plumbing, the Kaszubs were still getting by with kerosene lamps, contaminated wells, and backyard privies.

A fish shop made of several small, interconnected buildings. Signs for fresh or smoked fish are on several parts of the shop. In the background is a railroad car. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

By 1910, as the city’s population surged toward 400,000, there was an urgent need for two major improvements: a sewage treatment plant and an outer harbor. Jones Island was the obvious location for both.

In 1914, the city condemned the fishing colony. Family by family, its residents moved to the mainland.

In less than a decade, the number of dwellings plunged from more than 200 to just six.

Docks and shanties at Jones Island in 1938, with smokestacks and cranes in the background. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society)

Most of the holdouts lived on the river side of the peninsula. Their unofficial mayor was Felix Struck, a one-time fishing tug captain who had come ashore to run a weather-beaten saloon called the Old Harbor.

His time was finally up in 1943, near the midpoint of World War II, when Struck was evicted for reasons of what authorities called “port security.” The old fisherman moved to a new home on the South Side. Five months later, he was dead.

In a moment of inspired whimsy, the city turned the site of Capt. Struck’s last stand into a park and named it for the Island’s dominant ethnic group. Kaszube’s Park is the smallest in Milwaukee, about the size of a basketball court, but it occupies a unique place in the city.

In the midst of today’s manufactured landscape, the park is the last reminder that Jones Island was once a living, breathing human community.

==

SONGS:

“Kashub-Polish Waltz Medley” by Ray Chapeskie