At four weeks old, a trio of raccoons are just starting to open their squinty eyes.

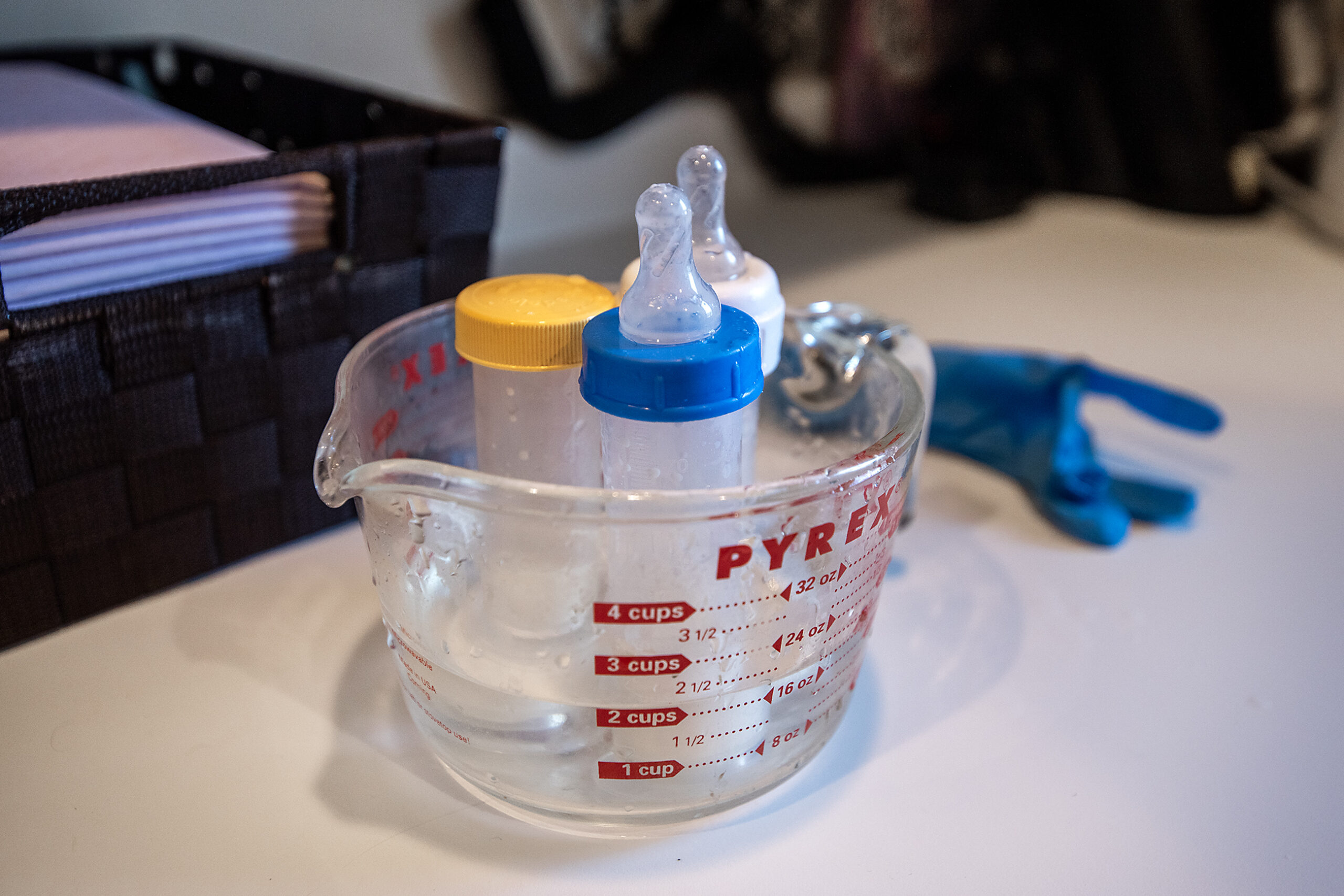

The kits were born blind, but are now beginning to respond to sights and sound. Jenny Esser fills a bottle with raccoon formula, and warms it up by running it under hot water. The fuzzy animals make chittering sounds, as Esser feeds them one by one.

Esser volunteers as a wildlife foster with Wisconsin WildCare. She’s part of a network of about 80 humans in south central Wisconsin, who serve as surrogate moms and dads to wounded or orphaned animals.

Last year, Wisconsin WildCare took in more than 1,400 small mammals in southern Wisconsin, including rabbits, opossums, squirrels and, yes, raccoons.

Jennifer Esser feeds a young raccoon formula with a bottle Wednesday, April 24, 2024, in Cross Plains, Wis. (Angela Major/WPR)

WildCare uses home-based model

Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources gives out licenses to people who rehab animals with the goal of eventually returning them to the wild.

Some rehabbers work at centralized facilities, like those run by humane societies.

But WildCare’s approach is a little bit different. Its volunteers open up their houses and apartments, offering the animals temporary shelter in human homes.

WildCare co-director Diane Goldensoph said the home-based model provides the group with extra space and flexibility, so it can care for more animals.

And, she said, it allows for a personal touch.

“A single caregiver’s positive in the sense that we put an eye on those animals every time we feed them,” she said. “As an individual, I can tell what the status is of the infants I’m raising. I can tell if they are having regular elimination. I can tell if they’re feeding the same as they did before.”

Jennifer Esser holds one of the young raccoons she fosters Wednesday, April 24, 2024, in Cross Plains, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Raccoon litter was abandoned after accident with chainsaw

In the laundry room of her house in Cross Plains, Esser keeps the raccoons in a small cage.

The raccoons’ mother fled earlier this spring, after a tree trimmer accidentally disturbed her nest. Three babies survived, but one had to be euthanized.

“One had been nicked with a chainsaw, and his injuries were just too severe to overcome,” Esser recalled.

Jennifer Esser holds a young raccoon foster before feeding it with a bottle Wednesday, April 24, 2024, in Cross Plains, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

Esser keeps notes about each foster raccoon’s weight, bowel movements and middle-of-the-night feedings. She marks each animal’s ear with nail polish, using different colors to tell them apart.

“This one’s pink,” Esser said, as she holds the litter’s only female. “I call her Queenie, and she’s queen bee of her brothers.”

Before completing training and undergoing a home inspection, prospective WildCare fosters — like Esser — go to an orientation. There, they gauge which animal is the best fit.

As a squirrel guy himself, WildCare President Tom Manley admits to having a bias.

“We also have an opossum director and a rabbit director and each of us stand up and give a little spiel beforehand,” Manley said. “That creates a little bit of an argument almost as to who’s going to be most influential in getting these potential new fosters to care for their animal.”

Per state regulations, each of the fosters must live within 60 miles of someone, like Manley or Goldensoph, who has an advanced wildlife rehabilitation license.

Those advanced rehabbers guide the fosters, teaching them things like how to keep the animals away from pets, and why they can only handle them while wearing gloves.

“It’s very critical for the animal to understand that humans aren’t their friends,” Manley said. “One of the biggest differences between a domestic and a wild animal is that you do have to back off and allow them to become wild.”

Raccoon decorations are displayed in the space where Jennifer Esser keeps raccoon fosters Wednesday, April 24, 2024, in Cross Plains, Wis. (Angela Major/WPR)

Spring is busy season for animal rehabbers

Each spring, WildCare gets flooded with calls. It’s when many baby animals are born, and it’s by far the busiest time of year for wildlife rehabbers.

“There comes a point in time when all our hands are on deck, and all of our arms are filled,” Goldensoph said.

As WildCare grows, it’s seeking volunteers, and not just those who want to serve as fosters. The group needs people to help with other tasks, including social media, marketing and transport, said Goldensoph.

And the organization is raising money with the goal of buying or leasing a facility that could be used to store supplies, and to potentially house animals in the short-term.

Bottles are prepared for the raccoon fosters Wednesday, April 24, 2024, in Cross Plains, Wis. (Angela Major/WPR)

Foster mom’s fascination with raccoon goes back decades

Esser, one of WildCare’s more experienced volunteers, estimates she’s fostered about 25 raccoons in total.

Her fascination with the bushy-tailed critters goes back decades. She’s drawn to the intelligence of raccoons, and to their dexterous, five-fingered paws, which look almost human.

When Esser was a teen, her brother came across a mother raccoon dead in the road, and he threw the surviving offspring into his car.

“It was crazy and wild because it was an older one,” Esser remembered. “I ended up getting it used to me by wearing thicker gloves, and it would follow me all over. I kind of took care of it.”

Years later, Esser is still watching over raccoons, though her approach is more regimented.

Raccoon fosters spend time in an enclosed outdoor habitat before returning to the wild Wednesday, April 24, 2024, in Cross Plains, Wis. Angela Major/WPR

By mid-summer, Esser will move her newest litter to a large pre-release cage that she built in her backyard. It has ropes and a kiddie pool to keep the raccoons occupied. Esser looped a chain over the cage’s door.

“We have to have extra locks, and some of our other rehabbers have said the same thing,” Esser said. ‘We call them Houdini. They figure out how to get out.”

In the fall, Esser plans to set the animals free into the woods near her house.

“I will not lie to you and say I haven’t cried,” Esser said. “You’re going, ‘Please go out and don’t let anything happen to you.”’

By then, Esser hopes all her midnight bottle feedings will have paid off.

She wants the raccoons to be fat enough to survive winter on their own.