Running a family business can instill pride and a valuable work ethic that circulates through the household. Wisconsin writer Nancy Jorgensen shares a story about her father, Quentin Smirl, and growing up around his printing business, Lithoprint Company in Waukesha, Wisconsin. She says it had a lasting impact on future generations of the family.

==

Fine Print

My dad’s work shirts—button-down, short-sleeved, white or blue—smelled like ink. The scent radiated, faint each morning when he wore a clean one, heavy in the evenings after a day in the shop. When ink dries, it releases the scent of aldehydes, ketones, and carboxylic acids. To me, it was the aroma of security, pride, and hard work.

My dad birthed his offset printing company the same year I was born — in 1954 — when paper companies and print shops flourished in Wisconsin. During the day, he ran jobs in another printer’s shop, and in the evenings, he operated his own press. He worked from our basement where paper and color became brochures, pamphlets, and books. While my mother fed and tended to me, he nurtured his other baby. Like twins, the business and I grew together.

Within a few years, my dad quit his day job and bought more presses, cameras, a cutter, folder, stitcher and drill. He mortgaged a building and created a press room, dark room, bindery, and office. He stocked paper, glue, and ink. An entrepreneur, he grew a business alongside his family and soon I had a brother and sister.

The business sent my siblings and me to college and in the summer between semesters, I worked in the bindery. My fingers studied the sensations of gloss, matte, and silk. My arms weighed the difference between a newspaper and the sheets of a magazine. As ideas and information became leaflets and publications, I inhaled the chemicals straight from their ink-soaked pages.

My dad chose a business for the future, a legacy for our family, a product that would always be in demand. Didn’t every college need a course brochure? Didn’t every auction need a catalog? Didn’t every city need a wall calendar?

He paid a fair wage to salesmen, pressmen, cameramen and secretaries. He carved room in the budget for donations — to local schools, to the park and recreation department, to the Schoenstatt sisters — in their long black habits — who needed materials for their retreats.

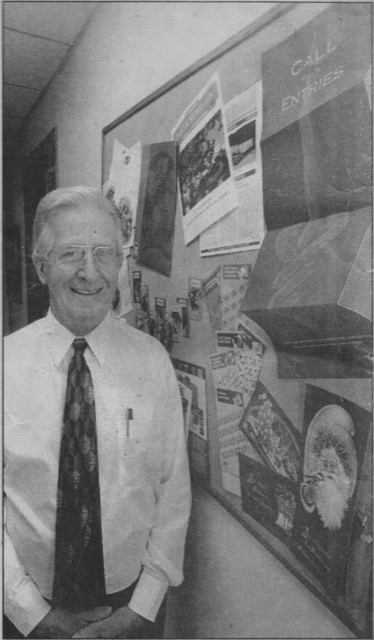

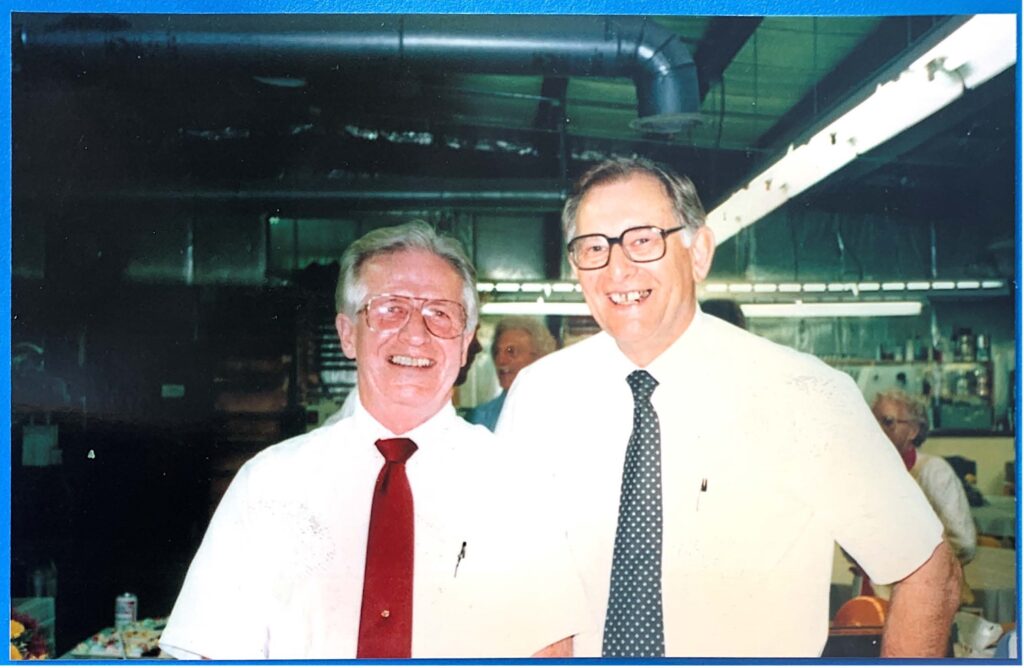

Quentin Smirl (third from left) with his partner (far right) and employees. (Courtesy of Nancy Jorgensen)

My dad died before the collapse of Wisconsin’s printing industry, confident he left my brother a profitable legacy. But when colleges and auctions and city governments moved information online — and print shops around the state folded — my brother said, “Dad would want me to face reality and make tough choices.”

My grandson, Stanley (2.5 years of age), learns songs from YouTube. He pinches a screen to watch a favorite show. He shouts at the alarm on my phone: “Hey, Google, STOP!” He is a child of Wifi, of FaceTime, of Instagram, of Twitter and his parents buy more broadband than number two pencils, more 4G than spiral notebooks.

But when Stanley is tired, he offers me his favorite book. “Grandma, read?” He strokes the fur on a page about animals. He screams siren sounds at a page about fire trucks. He sniffs the image of a rose on a page about flowers.

When Stanley is older, I will show him my drawer full of his great-grandpa’s work. Covers and insides shiny and black, or clean and white, or textured and variegated: relics of a not-so-long-ago time and a man who made an imprint.