Most days, I wake up and I’m just me, Jan…

a wife with a loving husband, a mom with three kids who alternately drive me crazy and supply the great joys in life, a teacher who prays daily that my passion for journalism will penetrate deep into my students’ psyches.

But then a chance remark, an encounter or a look, will transport me back…

It’s the late ‘60s and I’m helping my younger sister with her nightly bath. I sit, somewhat impatiently as she scrubs the day’s play from her knees. “What are you doing?” I ask. “You’re going to rub yourself raw.”

“I’m trying to get clean,” she says, her head bent over. “like Mom.”

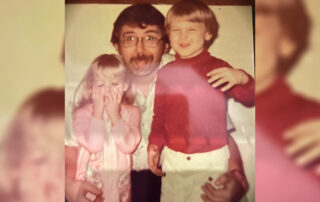

Our mother has pale pink skin that burns easily in the sun. Her six children come in shades of brown from tawny to cinnamon. The “dirt” my sister is so energetically trying to rub from her knees and arms is just skin.

As children, my siblings and I learned early that the color of our skin determined how others saw us. It would help some teachers decide how smart we were. It would help some neighbors decide if we’d get into college. In the case of my brothers, it would help some police officers decide whether they were up to no good.

I spent a good part of my childhood and young adult life working to prove that my skin color had nothing to do with my ability. I earned degrees from top schools. I won awards for my work.

When my new boss introduced me as “the newest woman minority faculty member,” I waited until we were alone to say something. “I would never introduce you as an old, white man,” I told him. “Why don’t you focus on what I’ve done?”

But the color of my skin was too much for him. He could not see me.

Then there was the well-meaning woman who joined a community discussion group focused on building bridges.

“It’s too bad we don’t have any minorities in our group,” she began. Puzzled, I interrupted, gesturing to myself.

“But I don’t think of you as a minority,” she responded. “You’re so smart and articulate.”

My ability blinded her. She could not see me.

More recently, a member of an accrediting team reviewing diversity in our department told my boss in an accusing tone: “And, you have a minority faculty member who doesn’t even look like a minority!”

Her expectations were her undoing. She could not see me.

For the most part, I’m at peace with such events – I’ve learned to see the world with my own eyes and my own heart. But I have hope for an easier path for those who follow.

Recently, I stood at the front of a room of elementary kids, a sea of faces, some white, some brown, some black. It’s part of a campus program for kids to attend classes with the hope of inspiring them to imagine themselves one day sitting in a college classroom. I had shared my background, but I wanted them to see me. My eyes fell on my 10-year-old self – a brown-eyed girl with cinnamon-colored skin.

“And,” I said, “You should know that before I was a Larson, I was Jan Micaella Mireles.”

Our eyes locked. She wiggled excitedly in her seat raising her arm high overhead, pointing down at herself as a grin spread across her face.

‘’Like me!”

She saw me. And in seeing me, she saw herself.