Way before cell phones, there were these things called telephones. And in the early days, a telephone call required a switchboard operator to make the connection. Writer Meg Jones tells the story a group of switchboard operators whose skill and courage on the front lines helped the US win World War I.

==

More than one hundred years ago, a group of patriotic Americans boarded ships in New York and headed off to war.

They wore U.S. Army Signal Corps uniforms, were fluent in English and French and were sent to France to fill a critical need in communications during World War I. The fact that they were female set them apart from the millions of other Americans in uniform in Europe.

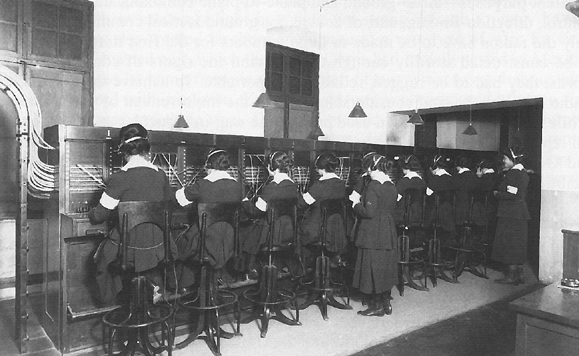

They were called the Hello Girls because of their jobs. They were telephone operators who handled calls by American and Allied troops fighting at the front throughout France. Just as radios were integral during World War II, in 1918 telephones were the military’s best way to communicate. And the country that led the world in telephone technology was the United States.

Here in America most phone operators were women. They sat at switchboards and connected calls by plugging in long cords. When General John Pershing arrived in France he quickly realized he needed experienced telephone operators, so he convinced the Army to send female volunteers. More than 7,000 women offered to go and 223 were ultimately selected and sent to France. In fact, two of the women were from Wisconsin: Martina Heynen from Green Bay and Hildegard Van Brunt from Milwaukee.

This was two years before women were allowed to vote in America.

Every command to advance or retreat or hold fire was delivered by telephone and it took an operator to connect that call. French officers frequently needed to communicate with their American counterparts and it was the Hello Girls who put those calls through and stayed on the line to act as simultaneous translators. Before they arrived in France, it was taking male phone operators as long as 60 seconds to connect a call. When the American women arrived, the timing was cut to 10 seconds.

As they quickly, calmly and efficiently handled numerous calls, they were privy to national security secrets and frequently served near the front lines. Some came under bombardment. Two phone operators never returned home, victims of the Spanish Flu epidemic.

The women were among the last Americans to leave Europe after the war, handling phone calls until the Treaty of Versailles was signed. Ultimately they connected 26 million calls and proved to be a significant factor in winning the war.

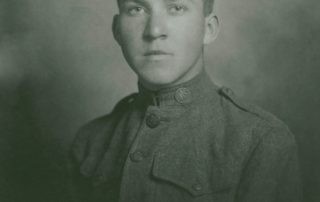

The arm band on Hildegarde Van Brunt’s arm shows she was an “operator” with the U.S. Army Signal Corps in France and Germany during World War I. Arm bands with a laurel wreath below a telephone meant “supervising operator” and ones with a lightning bolt were for “chief operators.” Credit – Family Photo

The Hello Girls were proud of the work they had done in France and when they returned home they tried to join veterans groups. When they were asked for their discharge papers, the phone operators contacted the Defense Department for the required paperwork.

And that’s when the Army told them they were not veterans. Even though they had signed oaths as members of the U.S. Army Signal Corps, worn uniforms, saluted officers, were frequently in danger and not free to leave whenever they wanted, the Army said basically – Oh, didn’t we tell you? You were just well-paid civilians.

Which was heartbreaking for many of the women. They didn’t get medals or bonuses given to every member of the armed services. They didn’t get medical benefits given to every other American who served in uniform during World War I. They couldn’t call themselves veterans or march in Memorial Day parades.

Some of the Hello Girls petitioned Congress and the military for decades and were repeatedly rebuffed in their attempts to be called veterans. Finally in 1977 President Jimmy Carter signed legislation recognizing what should have been done six decades earlier. By then only a handful of the phone operators were still alive. One of them told her family the long fight to become a veteran meant she could have something so many of her fellow phone operators had been denied – a flag on her coffin when she died.