Spearfishing is a tradition practiced every spring by Ojibwe tribes in northern Wisconsin. It’s a practice that’s been passed on for generations, and it’s part of tribal rights to hunt, fish and gather on lands ceded to the U.S. government under federal treaties.

Earlier this month, WPR’s Danielle Kaeding tagged along with a group from the Lac du Flambeau Band of Lake Superior Chippewa as they taught tribal youth the time-honored tradition.

==

Lac du Flambeau Tribal President John Johnson, Sr., said the tradition of spearfishing is at the heart of the tribe’s name.

“When the French came here, they seen our people out in canoes with torch lights. That’s why they call it Lake of the Torches here in Lac du Flambeau, or Waaswaaganing,” said Johnson.

Waaswaaganing is the Ojibwe word for the tribe, which Johnson says means “Lake of the Fire.” For hundreds of years, tribal members harvested fish by torchlight in birch bark canoes at night.

Lac du Flambeau Tribal President John Johnson, Sr., gets ready to take tribal youth spearfishing on May 7, 2022, at Little Trout Lake. (Danielle Kaeding/WPR)

As the sun sets over Little Trout Lake near Lac du Flambeau, Johnson and other tribal members prepare to take tribal youth out to spearfish for walleye, or ogaa. Before they head out, young kids take part in a drum ceremony.

They sing several songs, including one for tobacco, or asemaa. Johnson tells the kids to place tobacco in the water. Ojibwe language and cultural teacher Wayne Valliere explains Mishipeshu – a great water panther – protects the water on behalf of the Anishinaabe people.

Ojibwe language and cultural teacher Wayne Valliere stands next to Liam Armstrong, 9, before tribal youth go spearfishing on May 7, 2022. (Danielle Kaeding/WPR)

“When he sees the Anishinaabe putting their tobacco in the water, that makes him happy and pleasant,” said Valliere. “What that will do for us is that will calm the lake for us, so it’ll make it easy for the Anishinaabe to harvest and see the fish.”

The group of adults and kids loads up their boats with large tin buckets and aluminum spears around 12 to 16 feet long. Johnson is heading out with his 11 year-old grandson, Ganebik Johnson. Ganebik said he usually goes out with his grandad, who’s taught him to share what they harvest to feed their community.

“It’s important to Native people, and we do this to provide (for) our families,” said Ganebik. “And, we just hope we don’t get harassed.”

A little more than 30 years ago, hundreds of people harassed tribal spearfishers at boat landings in northern Wisconsin. They hurled rocks and racist remarks like “Spear an Indian, Save a Walleye” after a federal judge upheld tribal treaty rights to hunt, fish, and gather on off-reservation lands. While there’s no sign of trouble on this night, Johnson said not all people know or understand their rights.

“They don’t realize that we utilize the woods for our food, the lakes for food…and we try to save some for the next generation,” said Johnson.

Out on the water, Johnson guides the boat toward a spot near the shoreline where walleye are spawning. His grandson and grandnephew, Liam Armstrong, wear a helmet with a headlamp attached, shining the light from side to side on the shallow water.

“The eyes glow. That’s all you got to do is catch a glimpse,” said Johnson.

It’s not long before his grandson Ganebik spears their first walleye of the night. Nine-year-old Liam eagerly waits his turn.

“That’s what I want to do when I grow up,” said Liam. “Last year I got five walleyes, and it’s fun doing this.”

Tribal members take kids out in four boats that are each allowed to spear 25 fish per permit for a total of 100 fish. They count the walleye and measure them to comply with tribal regulations when they return to shore.

Ganebik Johnson, 11, helps his cousin Liam Armstrong, 9, while spearfishing on May 7, 2022. (Danielle Kaeding/WPR)

The typical harvest by tribal fishers on off-reservation lakes ranges between 30,000 to 40,000 walleye each year, according to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. In comparison, state anglers harvest five times as many fish with more than 200,000 walleye taken from the same lakes each year.

After returning to shore, tribal youth sit around the fire and swap stories about how many fish they speared. Ten-year-old Alina BigJohn of Lac du Flambeau said she speared two walleyes with the help of other tribal members.

“This is my first time being up there, and I want to come here next year,” said BigJohn.

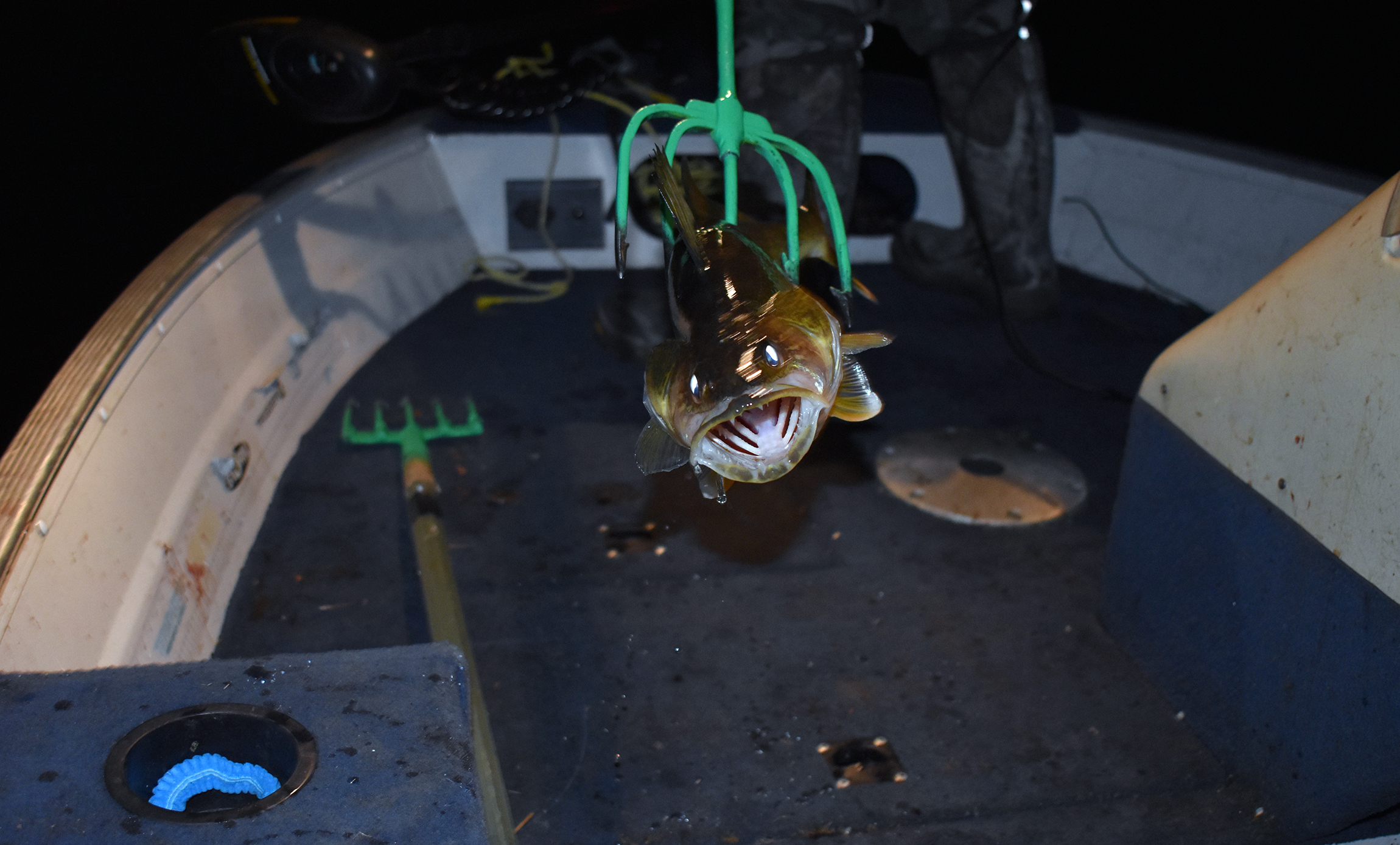

A walleye speared by Ganebik Johnson on May 7, 2022, at Little Trout Lake in northern Wisconsin. (Danielle Kaeding/WPR)

Eleven-year-old Ryan Mendez of Lac du Flambeau speared six fish and saw his friend spear his first walleye ever. Mendez said it’s cool they’re keeping this tradition alive.

“It’s a real great thing. I really appreciate it. I like it,” said Mendez. “I think it’s cool that we can all go in a boat, have fun times, and spear some walleyes. And, maybe see a big monster coming your way.”

Anna Sherwood, an Ojibwe language teacher aide at Lac du Flambeau Public School, said the kids are creating great memories while doing something healthy and taking part in their heritage.

“I think to be able to see that difference in where the fish are spawning in different lakes for first time spearers and have someone guide them through that and show them the differences, I think that’s huge,” said Sherwood.

Lac du Flambeau President John Johnson, Sr., stands nearby as a group takes tribal youth spearfishing at Little Trout Lake on May 7, 2022. (Danielle Kaeding/WPR)

Lac du Flambeau’s Sue Johnson said not all kids have parents who can teach them the tribe’s cultural traditions.

“That’s why I feel good about being out here,” said Johnson. “Seeing these kids sit around and enjoy cooking a hot dog on the grill and spearing a fish that they’re never going to get the opportunity to do if we weren’t here to do it for them, or help them.”

Both Sue and her husband John Johnson, Sr., said their hope is that these kids will learn their culture, language, and traditions to pass on to future generations.