When Geraldine Hines arrived on the UW-Madison campus as a law student 50 years ago, she had to adapt to the Wisconsin climate, the food, and its people. She had recently graduated from Tougaloo College in Mississippi and this was her first time living in the north.

“I was the oldest child in my family and the first one to go to college. Neither of my parents were educated,” said Hines. “So there were a lot of expectations for me and it was a really big deal that I got into law school. There was a lot of pressure to come here and succeed. That meant that I was a very serious student. But, I was young and not afraid of speaking my mind about things. I felt emboldened.”

While Mississippi was ground zero for the Civil Rights movement, there were also high-profile protests on the UW-Madison campus. Hines went on to participate in one of the largest protests in UW-Madison history, which took place fifty years ago this month.

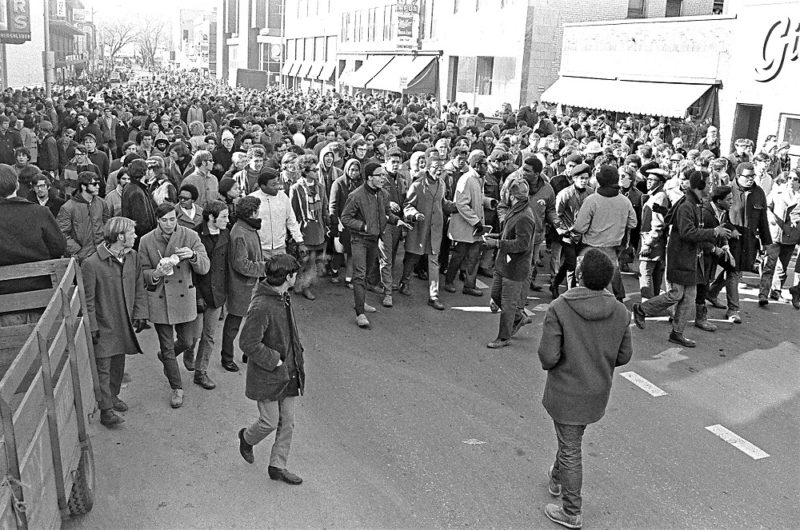

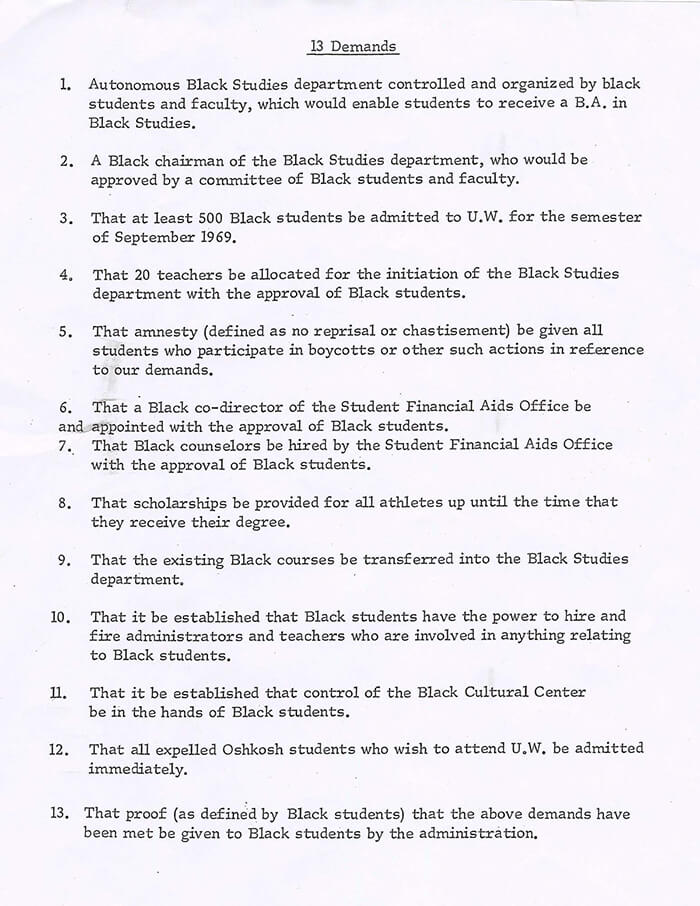

Striking students presented administrators with 13 demands, including the immediate enrollment of any expelled Oshkosh students who wished to attend UW–Madison. Ninety-four students at Wisconsin State College Oshkosh were arrested and expelled following a November 1968 protest that came to be known as Black Thursday. (Photo by John Wolf)

The Black Student Strike in February 1969 was fueled by a number of grievances black students had about their treatment on campus.

Organizers pushed for a campus-wide strike until a list of 13 Demands were met. Requests included admitting more black students and reinstating UW-Oshkosh students who were expelled after an equal rights protest. Hines said they were really energized around the demand for a Black Studies department with black professors.

“The other demands reflected the kind of disconnect that a lot of the black students felt from the university as a whole,” said Hines. “What can be done to make us feel a part of this University of Wisconsin-Madison family? It wasn’t so much, ‘We want you to do this!’ It was it was a way of expressing a desire and a need to be a part of what was happening here on the campus and not being seen as students.”

There were mass demonstrations with thousands of people marching through campus and down State Street. Participants disrupted classes and blocked people from entering buildings. Some students on strike didn’t go to class.

“We wanted to get people to pay attention to us,” said Hines. “This was all about young people trying to get an education.”

Students clashed at least twice with police and guardsmen, and police released tear gas on Feb. 13, 1969. (Photo by John Wolf)

While many of the demonstrations were peaceful, some scuffles broke out between protesters, non-participants, and law enforcement. Eventually, Governor Warren Knowles activated the Wisconsin National Guard.

After weeks of protests, the university agreed to one of the 13 Demands. They created the Department of Afro-American Studies. Some strike participants lost their scholarships in the aftermath.

Hines went on to be a lawyer after graduating from UW-Madison’s Law School. In 2017, she retired from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. She was the first African-American woman to serve on the state’s highest court.

The Legacy of the Black Student Strike

Recently, the University Communications and University Marketing teamed up with a group of journalism students, the Black Cultural Center, and The Black Voice to create an oral history project looking back on the Black Student Strike of 1969.

One of the students who interviewed strike participants for the project was Enjoyiana Nururdin, a sophomore majoring in journalism with a certificate in political economy, philosophy and politics.

“When we met with other students who participated in the strike in 1969, a lot of their reasoning for doing it was, ‘We didn’t have a choice if we wanted to fight,’” said Nururdin. “But I noticed a lot of students today, they’re more afraid of fighting because a lot of students are actually on scholarships. All students are dependent on going to school so that they can get a career.”

Nururdin said one reason she got involved in the reporting project was because black history is often overlooked in American history and she wanted to shine a light on this event. She also wanted to focus on the strike’s themes and draw parallels to campus involvement today.

“If a strike were to happen, how much of the white campus is going to support [black students]?” asked Nururdin. “Knowing how the climate is today, is the National Guard going to get called in? Is it going to be dangerous and are people going to feel safe? How much are people willing to risk if it’s not directly affecting them?”

“I think that’s a really important question: what’s changed in 50 years that would affect whether or not you could have that same kind of organization and fervor today?” asked Hines. “It just feels like it would be very, very difficult to get people to organize around something like that today and that’s kind of sad.”

Nururdin added, “I think it’s also different because we have these different platforms. A lot of people are on social media. They use their activism in different ways, which I think is good. But I think that same question stands. Are you willing to put your life on the line? Are you willing to lose your scholarship? Are you willing to be put in the situations that were ten times more dangerous 50 years ago?”

Nururdin said she’d like to see more black professors on campus and black counselors in the Financial Aid office. She said there are very supportive staff in the Black Culture Center.

“But where does that extend when you leave that safe space?” asked Nururdin. “There are a couple of different faculty and staff that are really supportive and really there for you. But I think it goes beyond just having a couple of people. It takes people who have a seat at the table to be able to bring issues to light and make sure that they’re being addressed.”

==

SONG: “A Change Is Gonna Come” by Brother Jack McDuff