We all learn lessons from our parents…how to cook a traditional family meal, how to have compassion or how to play an instrument. For Dr. Arif Ahmad of Madison, his parents taught him about optimism. The writer and cardiologist shares this poem about that lesson.

==

THE OPTIMIST

(June 2013, dedicated to my mother, Ismat Bano, and father, Abdul Majeed, for teaching me optimism)

Tough economic times, wars, famine, tsunamis, global meltdown, moral and ethical dehiscence.

So is the glass half-full or half-empty?

Enough going on to sap the energies, to drain the enthusiasm. Enough going on to cloud common sense.

But wait.

It refuses to be a pessimist. It believes in the human will, the human resilience, the human rebound.

It believes in the human race to stand up and deliver.

Every human being to be counted and ask, how can it better another life, how can it make proud mother earth, how can it first do no harm?

It is the good Samaritan, it is the human spirit, it is a dreaming child.

The question is, can it become I, we, us, yet again.

==

Dr. Arif Ahmad shared that writing about optimism, which he wrote in honor of his parents. He talked with WPR’s Maureen McCollum about the meaning behind the poem.

(This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity)

Maureen McCollum: You wrote this piece in honor of your parents. Can you tell us a bit about them? How did they teach you about optimism?

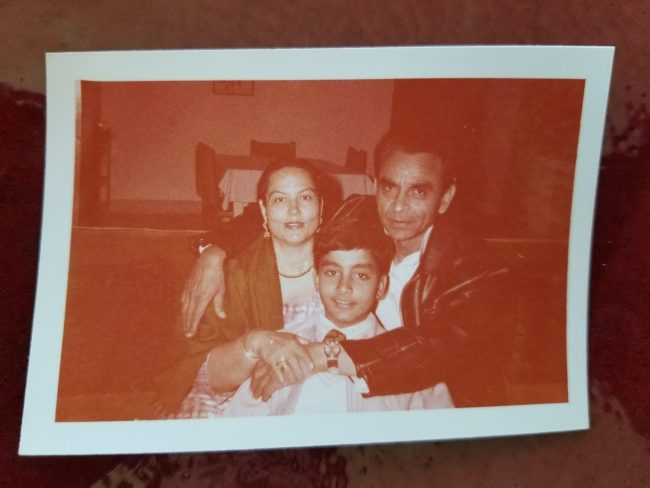

Arif Ahmad: My mom was a homemaker and my father was a civil servant. It’s interesting — I watched them live optimism. She had breast cancer in the 1980s, and it was diagnosed late. I watched her live her life for years fighting that disease and with great optimism. It never reflected upon me that she was so sick.

And then I saw my father — I think he is the most transformed individual I have seen. He rose from the lowest ranks of civil service, educated himself and kept educating himself until he reached the highest ranks. I have not seen a transformation that wide in one person in their lifetime. So I saw a lot of optimism in their living and that rubbed off of me.

MM: Why do you think it’s important to be an optimist?

AA: For our present and for our future, just like how my parents were optimistic through their struggles.

The piece talks about a dreaming child, which is a great example of optimism and I once was one.

I also believe that we hurt our better future when our policies as adults hurt the children — be it the wars or famine or disease or gun violence. I sometimes envy about a world where we can make policies and we can agree to act upon things which are good for the children everywhere, where we base our philosophies and policies on the well-being of children everywhere.

MM: How do you pass on optimism to your own children?

AA: So I say two things: One, I can’t control what comes at me, but I can control how I respond to it. And two, I’m a cardiologist. I know what the science says about optimism, which is it is critical for mental and physical well-being and for fighting disease.

There’s also another concept in the book which is ‘first do no harm.’ Being a Good Samaritan is great, but sometimes the best thing to do is to first is do no harm. This is something we live off of in our medical world, and that is also a point I wanted to bring up.